Kenedi Cain and Xavier Prater, who live 4 1/2 miles apart, are both dedicated high school students with high hopes for college — she wants to be a film director, he hopes to be an architect.

When COVID-19 hit and schools across the country closed their doors and transitioned to online learning, they both found themselves in the same predicament: neither had a computer.

But Xavier, 17, who lives in Grosse Pointe, Michigan, received a laptop from his school a few days after it closed. Kenedi, 16, who lives in Detroit, did not.

Months later, Xavier is carrying on with his schoolwork. He misses his classmates and school activities, but he’s keeping up with his SAT prep, and not much about his learning has changed.

Kenedi was finally loaned a laptop by a youth group she’s a part of in late May, but she’s sharing it with her four younger siblings. Choosing to prioritize their education over her own, she’s barely logging on.

Kenedi and Xavier are separated by not much more than a ZIP code, but educators say that’s enough to make a world of difference as the pandemic lays bare the existing disparities in the U.S. education system and worse, threatens to exacerbate them. The crisis, experts say, is likely to widen achievement gaps at public schools that serve disadvantaged children.

“It’s a tale of two ZIP codes,” Keri Rodrigues, president of the National Parents Union, said. “It is very, very different” for “students that live in urban communities versus your privileged, white, wealthy communities.”

“Where will I be by the time I’m a senior?”

Casey Edgar teaches 11th grade math to nearly 150 students at the Martin Luther King Jr. Senior High School in Detroit. Or, at least, she used to.

“The first week, I was in touch with, I would say, 50 to 60 percent,” she said. “And then the second week, it reduced to approximately maybe 30 percent. Now, it’s running at about 20 percent of the students I still talk to on a regular basis.”

When the Detroit Public Schools Community District transitioned to an online program — about a month after schools closed in mid-March — an estimated 90 percent of the students were, like Kenedi, without access to a computer or decent internet.

Printed packets were made available for students without those resources, but Edgar said the packets are likely of limited usefulness for students who aren’t able to connect with their teachers. “What good is a packet if you don’t know how to do it?” she asked.

In April, the school system secured a $23 million donation from local businesses to provide a laptop and six months of internet access to each one of Detroit’s roughly 50,000 public school students, but the laptops are not expected to be distributed until late summer, long after the school year has ended.

In the meantime, the months of lost learning for students not receiving face-to-face instruction, or receiving less of it, is expected to take a steep toll on an achievement gap that already plagues many Detroit students.

“I expect it to be exponential,” said Edgar, who thinks the lack of engagement is the consequence of a few things, namely that many still lack the tools to log on, and that because students aren’t being graded, there’s less incentive to keep participating.

But down the road, in Grosse Pointe, the school district had a laptop in the hands of every student who needed one within days of schools shutting down. At last count, the district said 93 percent of high schoolers were actively engaged in online learning.

In the Detroit school system, engagement in the online learning program is hovering at 50 to 60 percent, according to the district. That figure doesn’t count students who may be filling out printed packets of schoolwork in lieu of online assignments, but it still amounts to nearly half of the district’s 50,000 students not regularly getting instruction from their teachers.

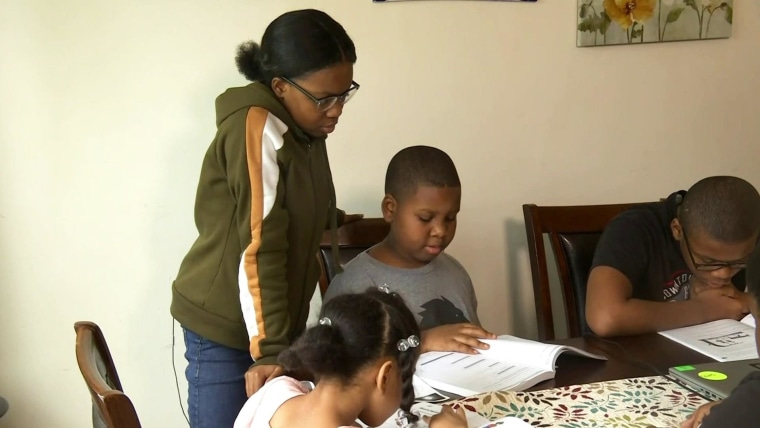

Kenedi is one of those students. A sophomore at the Cass Technical High School, one of Detroit’s best high schools, she was left with two options when school shut down — try to do her schoolwork and video chats with teachers entirely on her phone, or share a computer with her four younger siblings, who all have their own schoolwork and their own scheduled video chats with teachers.

“I have four classes throughout the day that I have to attend at different times, and my brothers do as well, and a lot of those times cross each other or they’re at the same exact time,” she said.

Kenedi’s parents are both essential workers, which means that she’s in charge of her siblings for most of the week.

“I like to think of myself as the third co-parent,” she said. The teenager occasionally works on packets of schoolwork, but made a decision to put her own education on the back burner so that she could home-school her siblings on that one computer.

“Whoever doesn’t have the computer on the specific day, I give them little stuff to keep their mind going,” she said “So my youngest brother, I usually have him write a story about the day before, or tell me something about, you know, his favorite food.”

Still, Kenedi said sometimes worries creep in about what this will mean for her future. She received a 4.0 grade point average on her last report card, but that achievement was hard earned.

“I’m trying to keep good spirits, but I mean, it’s certain stuff that I don’t have a choice but to think about,” she said. “One being, where will I be by the time I’m a senior? Will it be hard for me to get into college even with my [advanced] classes?”

Kenedi said she likens the situation to living in an empty, decrepit house beside someone who owns a mansion and has limitless resources.

“He gets whatever he wants, whenever he wants, whenever something wrong happens,” she said. “And it’s just like, wow, why can’t we be like that? Or why can’t we step in and give to our students like they are because our students are no different from theirs.”

Without the necessary resources, Kenedi and other Detroit students have been forced to make hard decisions about their education.

Lacking a laptop, King High School junior Azane Scott used her phone to connect with teachers and write essays when she wasn’t babysitting her infant brother. But when her grandmother died in late April, she put her lessons aside. She didn’t start logging on again until mid-May, when her mother bought her a laptop.

Quincey Strickland, a Communication and Media Arts High School junior, also began doing schoolwork on his phone but said the device wasn’t adequate for productive learning. Eventually he gave up, and as of late May, hadn’t done any schoolwork in over a month.

Ridgeley Hudson, a King High School senior and a board member on the school district council, said the lack of resources has left many students feeling discouraged.

“It doesn’t take the coronavirus to highlight the disparities between the suburbs and the city. We knew that they have been treated far better than we have,” Ridgeley said. “It’s like they get things first and we get the scraps.”

“That’s just money and who has it and who doesn’t.”

Detroit is far from the only city dealing with these disparities.

In the D.C. Public Schools, when schools closed in March, the district estimated that 30 percent of students didn’t have access to a laptop or a tablet in the home. A spokesperson for D.C.’s teachers union said that number was likely too low an estimate.

The Chicago Public Schools system provided laptops to 122,000 students, bringing its percentage of students with digital access up to 93 percent. But only 84 percent of students were handing in assignments during the week of May 11.

The Detroit Public Schools Community District superintendent, Nikolai Vitti, believes that his students will incur about six months’ worth of learning loss as a result of the coronavirus shutting down schools.

“I think our students have taken a step back, unfortunately, because they’re not experiencing the regular, face-to-face instructional interaction,” Vitti said. “Obviously there’s a level of volunteerism that goes along with this period of learning. And based on the home situation of the child, learning may not be happening.”

Vitti said laptops are only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the ways in which children in low-income districts are suffering due to the coronavirus.

“There are so many other issues that our families, and therefore our students, deal with that’s not education. Where will folks live? Are they paying the light bills?” he said. “Those are basic needs that get in the way of thinking, ‘I have a test on Wednesday that I have to study for,’ or, ‘What’s my GPA need to be to get into that college?’”

“Whether you’re talking about devices, you’re talking about technology in a classroom, you’re talking about arts, music or teacher salaries, we’re at a disadvantage,” Vitti added. “That’s just money and who has it and who doesn’t.”

He’s not wrong. Local funding for Grosse Pointe students is far higher than in neighboring Detroit— $4,876.82 compared to $823.38 per student, according to the National Public Education Financial Survey. Vitti estimates that if Detroit used the same funding formulas that the neighboring suburbs do, the school district would have $160 million more in funding.

Detroit students do receive more in state and federal funding, but federal dollars come with strings attached. In line with those restrictions, Vitti said Detroit has largely used these funds to hire additional support staff —such as guidance counselors and reading coaches — because the federal money can’t be used to dramatically increase teacher salaries or to improve the facilities.

“What’s happening is the federal dollars are serving as a way to fill a large gap that is created — or perpetuated — by how states are funding districts,” Vitti said.

“We know that lawmakers, politicians, and even other communities believe that certain kids are more important than other kids based on the color of their skin and the ZIP code that they live in. And that’s it. That seems very simplistic, but that’s ultimately what we’re talking about.”

The situation could be about to get worse. A number of states, including Michigan, have discussed budget cuts due to the economic downturn caused by closures and shelter-in-place orders. Because education often makes up one of the biggest costs in a state’s budget, education advocates worry it could be on the chopping block.

The Council of the Great City Schools, which represents the country’s large urban school districts, is anticipating that 275,000 big-city teaching jobs will be lost next year due to budget cuts.

Budget cuts are all the more concerning because public schools will be attempting to do more with less. In addition to the costs of personal protective equipment and socially-distant classrooms in the fall, education funding in many states still had yet to recover from the Great Recession.

According to an analysis by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, when COVID-19 hit, K-12 schools across the country were already educating 2 million more students with 77,000 fewer teachers than before the recession.

Despite preparing for a shortfall of about $40 million due to the statewide budget cuts next year, Vitti is confident that he can avoid layoffs. In May, the district announced that the Detroit public school system was increasing its starting salaries for teachers to $51,071 to better attract staff.

“We had a lot of ground to make up even before COVID,” Vitti said.

One boon for the district is an expected $80 million infusion of emergency federal aid from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act, or CARES Act. Spread over a period of two years, the aid will be just enough to plug the gap left by budget cuts, but not enough to enhance any of the district’s programs or pay for additional COVID-related costs, which are expected to be exorbitant, Vitti said.

“All COVID has done is put a magnifying glass on inequity in this country, from a race and socioeconomic point of view,” he said. “Any time we have tragedy in this country, it negatively affects everyone, but it affects those that are poor, and those of color more, we know that. And COVID is an example of that. Detroit is an example of that.”