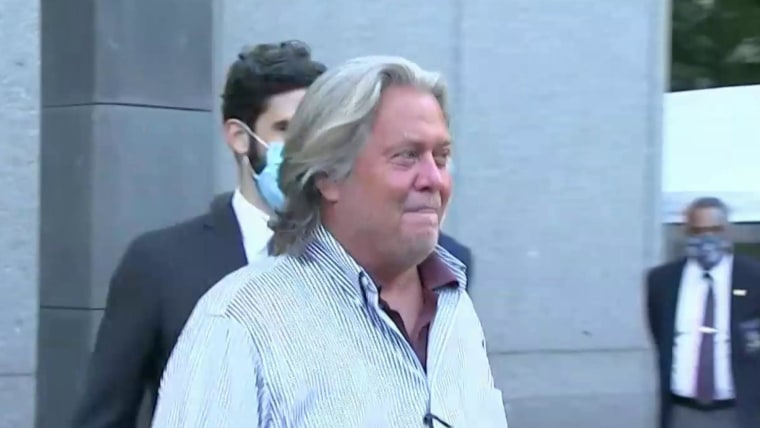

Steve Bannon, President Donald Trump’s former adviser, and three associates were charged Thursday with defrauding hundreds of thousands of donors in an online crowdfunding campaign that raised more than $25 million toward building a wall on the southern border.

As part of their pitch, they assured the public that 100 percent of the funds raised would be used “in the execution of our mission and purpose,” the indictment reads.

One-hundred percent? That ambitious a claim — that every dollar collected will go toward the cause at hand — may be what attracted the attention of federal regulators, even before the first dollar was collected. That’s because a 100 percent promise is so difficult to achieve, and so unlikely to accomplish, that the pledge itself is a red flag to investigators.

The indictment alleges that, starting at the end of 2018, one of Bannon’s co-defendants, Brian Kolfage, an Air Force veteran and Purple Heart recipient, launched a fundraising campaign called “We Build the Wall” on a crowdfunding website directing donors to send money for the wall effort.

“To induce donors to donate to the campaign, Kolfage and Bannon,” the indictment reads, “falsely assured the public that Kolfage would ‘not take a penny in salary or compensation’ and that ‘100% of the funds raised will be used in the execution of our mission and purpose’ because, as Bannon publicly stated, “we’re a volunteer organization.’”

Donors were allegedly promised that if the campaign could not attain its goal, it would “refund every single penny.”

In fact, the indictment alleges, Kolfage received some $350,000 for his own “personal use” while Bannon, the indictment alleges, received $1 million routed through a nonprofit organization he controlled that was used to “secretly pay Kolfage and to cover hundreds of thousands of dollars in Bannon’s personal expenses.”

The defendants are charged with conspiracy to commit wire fraud for allegedly misleading donors. They are also charged with money-laundering for allegedly concealing the source of income, payments or other benefits they received all of which was exacerbated by the fact that they promised not to receive income in the first place.

A 2019 study by Forbes magazine found that even the top charities in the world very rarely achieve what is known as 100 percent fundraising efficiency — that is the percentage of donations remaining after subtracting costs of obtaining them — or 100 percent charitable commitment, in other words, the amount of the funds gathered that are fully directed to the charitable purpose, rather than overhead expenses. Charities known as “gift-in-kind“ charities are able to achieve high efficiency scores by accepting noncash donations like food, clothing, equipment and medical supplies. It’s hard to subtract costs from a can of food or a blanket. Bannon and his co-defendants were not collecting cans or blankets, however. They were collecting money.

What’s peculiar about the Bannon case is that defendants didn’t have to make these ambitious claims. The IRS allows charities to spend money on overhead and administrative costs; it’s not illegal to spend a percentage of funds on the charity’s salaries and expenses. But even if a charity spends a whopping 35 percent of donations on overhead, it’s doubtful that yachts and other luxuries would be considered legitimate expenses of a charity. Irrespective of what percentage goes to the charitable purpose, it is illegal to make misrepresentations to deceive donors out of their money.

According to the same Forbes study, the average fundraising efficiency for the top 100 charities in 2019 was 91 percent, with the top charity slightly below the average at 90 percent. The Better Business Bureau suggests charities spend a minimum of 65 percent of their total expenses on program activities—a much lower figure than the highest-ranked organizations.

In other words, Kolfage, Bannon and the others could have promised 92 percent of funds would go to charitable purposes. They would have done better than the 2019 average and better even than the top-ranked organization. If they raised $25 million, they could have safely spent some $2 million (8 percent) on costs of fundraising. Instead, it appears these “100 percent” promises left these defendants with 0 percent room to avoid law enforcement scrutiny.

It’s not the first time a charitable organization has gotten in trouble after making “100 percent” promises. In 2016, federal prosecutors in Florida convicted a man named Gary Tomey of conspiracy to commit mail fraud and wire fraud, by using deceptive and misleading telemarketing tactics to solicit charitable contributions, under the pretext that the contributions would be used to provide services to abused women and needy children in each donor’s state. In Tomey’s case, prospective donors to his organization were told “100 percent” of each donation “goes directly to the charity.” That statement was technically true because donations went directly to the defendant’s organizations, several of which had nonprofit status. However, the statement was also deemed purposefully, and illegally, misleading: Numerous donors believed 100 percent of each donation would be used for charitable purposes which is not the same thing. What they heard was that each donation would go “to charity.”

The federal court in Tomey’s case noted “the law forbids material misrepresentations that are ‘reasonably calculated to deceive another out of money or property.’” The telemarketers in Tomey’s case thus were deemed to have deceived donors into believing that 100 percent of their contributions would be used to support charitable activities. Just as in the Bannon case, telemarketers in the Tomey case were instructed to tell prospective donors that all fundraising for the charity was done by “volunteers.” In fact the callers were paid employees. The government alleges Bannon publicly stated, “We’re a volunteer organization.”

Each of the charges carry a maximum penalty of 20 years in prison. Bannon is not likely to serve anywhere close to that amount of time. He’s presumably a first-time offender.

Further, while COVID-19 has devastated the United States, older offenders charged with nonviolent crimes who have been sentenced during the crisis have been handed lesser sentences with an eye to the idea that COVID is rampaging through prisons.

Still, if Bannon is convicted of defrauding Americans out of millions of dollars, even the novel coronavirus might not keep him out of prison.