Politics are hard to miss on YouTube this year.

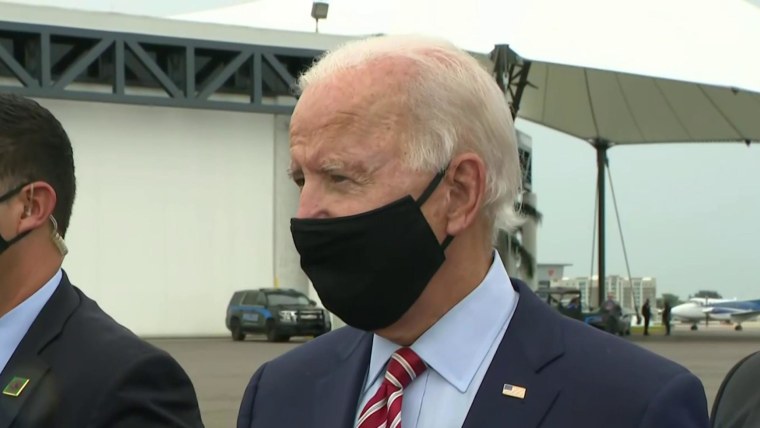

Last month, Joe Biden made a splash when his campaign bought out YouTube’s homepage with an ad about sports stadiums that had been left empty by the coronavirus pandemic. The ad got more than 10 million impressions, his most ever on the site.

President Donald Trump’s campaign has purchased YouTube homepage ads, too, and he reserved the space again for early November as voting ends, Bloomberg News has reported. The ads are autoplay, making them all but unavoidable.

Beyond those ads, politics are popping up in all sorts of videos. A legion of well-practiced right-wing YouTube personalities, some with large followings, have been posting daily videos boosting Trump and launching attacks against Biden. And digital strategists for various political campaigns are exploring ways to seep political discussion deeper into YouTube’s niche audiences, placing ads alongside cooking shows, for example. Others are working on campaigns that ask for donations, which used to be less common on the site.

YouTube, founded in 2005, has often been overshadowed by the likes of Facebook and Twitter as a place where political campaigning happens online, but this year is shaping up differently, and the fall promises to test YouTube’s capacity to serve as a political referee.

“YouTube has come into its own. It has blossomed. It is incredibly effective,” said Rebecca Donatelli, president of Campaign Solutions, a political consulting firm that works with Republican candidates. In the realm of politics, she said, “this is the year of YouTube.”

Trump himself has more than tripled his YouTube following in five months, growing from 320,00 subscribers in April to more than 1 million now. Politico reported this month that the Trump campaign was trying to flood YouTube with content and leverage the site as a secret weapon, much as the Trump campaign did with Facebook in 2016.

But the Biden campaign says it has doubts. Megan Clasen, a Biden campaign adviser, tweeted that it had outspent Trump on YouTube at the start of September.

In a sense, it’s about time YouTube got so much attention. It often ranks first or second on lists of most-visited websites, and it’s the most widely used online platform among U.S. adults, a Pew Research Center survey found last year.

It may be that 2020 is an especially good year to match with YouTube as a medium. News about police shootings, Black Lives Matter protests and the coronavirus pandemic is often highly visual.

“That’s where the electorate is this cycle, and if it doesn’t have a video attached to it, it’s not as real,” Donatelli said.

But YouTube’s emergence as a central political battleground is causing alarm among advocates for voting rights, as well as people who research disinformation online, who fear that the Google-owned service is underprepared for election season.

They point to a growing body of research that has identified YouTube as a primary way people learn to believe conspiracy theories or consume extreme commentary, sometimes fueled by YouTube’s recommendation algorithm.

“I still think they really haven’t figured out with YouTube how to stop those who are profiting off misinformation and disinformation from continuing to do it,” said Joan Donovan, research director of the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy at Harvard University.

YouTube said it is taking the challenge seriously. Leslie Miller, YouTube’s vice president for public policy, wrote in a blog post last month that the service was committed to removing content that violates its rules, such as videos that encourage others to interfere with voting.

The company has outlined other steps to ensure a credible election, such as pledging to terminate channels that misrepresent their countries of origin or conceal their associations with government actors. YouTube has banned videos promoting Nazi ideology and promised a crackdown on “borderline content.”

“Over the last few years, we have developed a systematic process to effectively remove violative videos, raise up authoritative content and reduce the spread of borderline content. We apply this framework to elections around the world, including the 2020 U.S. election,” YouTube spokesperson Ivy Choi said in a statement.

The primary season saw at least one example of a political dirty trick carried out on YouTube. Last month, as polls opened in Florida, some voters received fake text messages and a YouTube video falsely claiming that Republican congressional candidate Byron Donalds had dropped out. YouTube removed the video, and Donalds prevailed in the primary.

But YouTube’s policies still lag behind those at Facebook, Pinterest and Twitter, according to a report card from the Election Integrity Partnership, a group of academics and nonprofits tracking misinformation online. The group says YouTube’s policy on voter intimidation, for example, isn’t comprehensive enough.

It’s not just Nazis and voter intimidation that worry people, however. It’s also how YouTube shapes the broader information ecosystem.

More so than in 2016, YouTube is a home for livestreamers and social media celebrities who have built followings of thousands or millions of people. YouTube shares revenue with them and offers other opportunities to make money that other tech platforms don’t match.

Donovan of Harvard said she expects some YouTube provocateurs to wield newfound media influence over the next two months, backing one candidate or another. “And we’re not going to know if those influencers are being paid by companies, charities, dark money groups or super PACs,” she said, because political operatives may be able to avoid disclosure requirements from the company, the government or both.

In February, the Democratic primary campaign of former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg helped to popularize new marketing forms, such as endorsements from social media meme accounts.

“There’s a shadow market for political advertising that is potentially going to be supercharged in the lead-up to the election,” Donovan said. If YouTube can’t keep up, she said, “the whole of society suffers.”

Voting rights lawyers worry about the spread of false information about how to register or how to vote. In a report this month, the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University Law School urged tech companies to increase the visibility of reliable sources, such as election agencies.

When people search for voting information, “some video gamer shouldn’t be the No. 1 result,” said Ian Vandewalker, senior counsel at the Brennan Center.

Trump’s courting of YouTube influencers was on show last year when he invited many of them to a social media summit at the White House. They now make up something like a YouTube cheering section, often popping up on the most-viewed list with a search for Biden’s name.

Covid-19 has only added to the value of streaming services like YouTube, said Shannon Kowalczyk, chief marketing officer for Acronym, a group that’s working to elect Democrats including Biden.

“People have more time on their hands at home. We’ve seen streaming numbers surge,” Kowalczyk said. Acronym uses YouTube to target people, especially young people, who don’t normally tune in to political discussions and may be in a position to be persuaded, she said.

YouTube and Google surprised many digital ad buyers last November when they said they wouldn’t allow political campaigns to target ads based on public voter records or political affiliations. They said ads would be more widely available for public discussion.

That caused some money to shift to other platforms that allow narrow targeting, such as Roku, strategists said. But they’re also finding YouTube useful in unexpected ways.

“We’re using it a lot for fundraising, which is way different from what it has been in the past. It was mostly a persuasion play,” said Eric Frenchman, chief marketing officer for Campaign Solutions, the Republican firm. He said the return on investment rivals that of Facebook, where campaigns have typically gone in the past to raise money.