The Atlas of Ancient Rome, ed. Andrea Carandini, Princeton University Press, 2 vols., 1280 pages.

Rome holds a special place in the tradition of Western urbanism. Its forms, its colors, and its layout transmit echoes from an ancient past. Its iterations and enclaves are way stations between antiquity and our own time. Today, as ever, Rome is a city of deep-green Mediterranean scrub, red tufa, and fast-changing skies; a city of busy markets and public fountains; of seafood and wine. An eternal city, yes—but also one whose mood is always contingent upon the present. An afternoon rain soaks the cobblestones and runs off the awnings, and then the sky is all watercolors.

Rome holds a special place in the tradition of Western urbanism. Its forms, its colors, and its layout transmit echoes from an ancient past. Its iterations and enclaves are way stations between antiquity and our own time. Today, as ever, Rome is a city of deep-green Mediterranean scrub, red tufa, and fast-changing skies; a city of busy markets and public fountains; of seafood and wine. An eternal city, yes—but also one whose mood is always contingent upon the present. An afternoon rain soaks the cobblestones and runs off the awnings, and then the sky is all watercolors.

Today, the center of Rome, graciously, shows little evidence of the late-20th century. Renaissance churches may stand beside shops pushing the latest sartorial and culinary offerings, but the city’s development seems to have jumped from Hemingway’s time to our own, skipping over the superblocks of modernism and keeping its traditional urban fabric intact. From certain prospects, as where pathways from the Campidoglio look out over the sprawling ancient Forum, this pattern may create a superficial impression that everything within view is simply old. And, with few exceptions, this is true. But, the layering of so many ages is richer and more mysterious than meets the eye.

From our distant perspective, we may be tempted to collapse the many generational layers that shaped the ancient elements of the city into a single phenomenon. Or, in another approach, authors like Jérôme Carcopino have focused on a particular moment in history to create a less unwieldy urban narrative. (Carcopino chose the late first and early second centuries, A.D.) Yet the more recent Atlas of Ancient Rome, edited by Andrea Carandini and first published in 2012, represents a sharp counterpoint to the impulse to simplify. Rather than attempt to fit the ancient city to the limits of working memory, it uses the latest spatial and database methods to give order to the stratified complexity of urban growth and change.

The Atlas depicts a living city over a period of more than a thousand years. Its temporal breadth flows from its research context: Rather than a mere survey of existing knowledge, the Atlas was distilled from a much broader landscape of ambitious research, documentation, and analysis. Carandini, now 81 and professor emeritus of archaeology at Sapienza, led this work with a team of younger scholars who contributed heavily to the Atlas. In his introduction, Carandini laments the dormant (or at best neglected) state of what he calls topographical scholarship of Rome. Prior to the Atlas, no map of a such broad scope had been completed since Rodolfo Lanciani had created the Forma Urbae, a 46-plate atlas, between 1893 and 1901.

Having identified a need, Carandini articulates the laudable goal of applying 21st-century technologies, especially GIS (geographic information systems) and CAD (computer-aided drafting), to render a new realm of topographical analysis of the ancient city. With its precision and its layering abilities, these types of three-dimensional modeling allow scholars to pursue a uniquely multifaceted approach to the archaeological knowledge that has been collected, but not always contextualized, since the dawn of modern classicism. The Atlas, to Carandini, is simply the first major product of such an effort. He floats the ideas of a virtual, interactive Atlas—or similar atlases of other historical cities—as future possibilities.

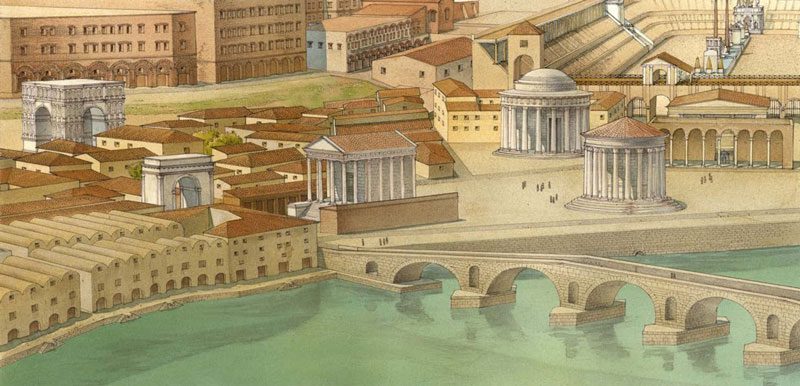

The Forum Boarium in the late imperial period, as seen from Tiberina Island. The Atlas of Ancient Rome (Courtesy of Princeton University Press)

The first edition of the Atlas was published in Italian, in 2012, and an English translation followed, from Princeton University Press, in 2017. Future possibilities aside, the Atlas itself is an ambitious project: a two-volume, hardcover set with more than 1,100 pages of essays, color images, technical drawings, and maps. The richness of is immediately apparent. Art and photographs punctuate the otherwise text-oriented first volume, while maps, site plans, and sections define the second. One senses that even at 1,110 pages, the available material has been compressed.

The detail and precision of the Atlas are extensive and impressive: As in Lanciani’s work, every inch of the ancient city’s physical footprint is covered in Carandini’s. Here, this means all of the urban land that was enclosed by the city walls in the third century. Within this context, countless individual monuments, buildings, and outdoor sites are illustrated at higher resolutions in plan-and-section form. All drawings are color-coded to distinguish between extant structures, archaeological records, and scholars’ presumptions; and to date as much of the evidence as possible.

Templum Pacis hall of the Forma Urbis. The Atlas of Ancient Rome (Courtesy of Princeton University Press)

The written parts of the Atlas are thorough and serious. A collection of scholarly essays provides narratives of the ancient city’s infrastructure networks, building methods, natural environment, and demographic trends. Chapters on each of the 14 Augustan regiones—essentially, its political wards—are methodically organized, beginning with notes about urban planning, and proceeding to histories of urban change across the span of classical antiquity. The methodology used to collect and organize the information contained in the Atlas is also discussed at length—creating a degree of transparency between the editor and his readers that is refreshingly candid.

Presumably, Carandini and his team would agree that a project that draws on such a wealth of information will pose challenges when salience must be assigned to selections. In this respect, the Atlas occasionally falls short: In an effort to be evenhanded, some of the city’s most interesting points of interest do not get enough ink. For instance, the Suburra, a sprawling slum of the classical city that foreshadowed those of the industrial age, is not explored in much detail, either with respect to its role in housing the poor or its setting for some of the earliest building codes. Maps and drawings of the city’s engineering marvels (e.g., aqueducts and sewers), are less thorough than they could be.

Campus Martius, including the Theater of Balbus. The Atlas of Ancient Rome (Courtesy of Princeton University Press)

Ironically, while the Atlas celebrates one of history’s most organic, ad hoc cities, its own organization shares an approach with 20th-century zoning in its attempt to impose an oversimplified order on an intrinsically complex subject. For instance, its content is sorted into broad categories rather than contextualized in a messier but more satisfying way. (As a result, the separation of essays (in vol. 1) from plans, sections, and maps (in vol. 2) does not make for the easiest cross-referencing of context and details, while a decision to examine the city through the lens of its 14 Augustan regiones does not encourage the most honest exploration of its integrated, continuous urbanism.)

Such things make Carandini’s thought of an interactive, virtual Atlas more appealing. Given the wealth of information on which the Atlas was drawn, a printed version—even at 1,100 pages—feels at times curated. In fact, the editor describes the Atlas as a virtual museum of the city (which has no brick-and-mortar institution devoted to its ancient topography). It would be fascinating to delve into these sites at various scales, to explore direct links between essays and related imagery, to analyze geospatial data for new patterns, or to reorganize the layering and visibility of elements on a particular map, plan, or section.

Ultimately, the Atlas, and its underlying research, adds value to our cultural landscape. It begins to fill a void that, as Carandini notes, has persisted for too long. Many Italian Renaissance writers expressed the architectural thinking of their time, and from their books we can learn the context of their visions and revisions, and how the work of their time was shaped by an understanding of the forms of classical antiquity. Leon Battista Alberti, Sebastiano Serlio, Andrea Palladio and others told that piece of the story well—and much of what they have said can be confirmed, or intuited, with one’s own eyes. The written and physical links between the quattrocento and our own time are intact.

The mystery of Rome’s urbanism—the part most shrouded in shadows—lies in what is inherited from its truly ancient past. We know that many of the forms and structures still exist; we know, roughly, what purpose these places served, and how they correspond with the customary elements of urbanism in the modern West. Yet Vitruvius remains an enigma, and no other ancient author’s comprehensive record survives. The Atlas of Ancient Rome, through literal concrete details, shows what close, iterative study since the 1400s has clarified, by correlating disparate bits of knowledge with a single place.

Carandini’s team has built the most comprehensive model, to date, of an ancient city. What comes next will turn on how this is put to use. The focus on Rome’s topography could as well be described as an exploration of its multilayered urbanism. The intricate relationships between infrastructure, streets, squares, monuments, temples, baths, marketplaces, and private realms are depicted at a level never before seen. A close parallel might be found in the early-20th-century Sanborn Fire Insurance maps that show the granular forms of American industrial urbanism in the period before zoning. The Atlas depicts the original case of large-scale, traditional Western urbanism (including its customs, patterns, and evolution) in similar relief.

The importance of classical Rome to the conscious and unconscious customs of later Western urbanism cannot be overstated. Today, as cultures cross-pollinate, and as technologies topple timeless ways of living, it is an open question whether the familiarity of Rome’s ancient forms will be felt much by those who live in the future, beyond the next horizon. Yet, at least for now, for many of us, the artifacts and patterns that come to life in the Atlas remain contextualized by some tenuous, collective memory; some sense that these mysterious patterns, finally reduced to print, could have shaped the ones we find so familiar.

Perhaps this time—our time—is really the end of the ancient world.

Theo Mackey Pollack practices law in New Jersey, and is a consultant on urban-planning projects, including Hurricane Sandy recovery. He blogs at legaltowns.com.