WASHINGTON — The Democratic presidential primary is about to super-scale, moving from a series of single-state battles for momentum to a national multi-front war for delegates, putting extra pressure on underdog campaigns that can’t raise massive amounts of money or field large armies of supporters in dozens of places at once.

Half the states in the county will vote this month, making the person-to-person politics of the small early states no match for the more-is-more style of campaigning needed to win mega-states like California, Texas, Florida and Illinois, which all vote this month.

The scale of the upcoming contests is enormous. About 10 times as many delegates are at stake on Super Tuesday as were up for grabs in Iowa, New Hampshire, Nevada and South Carolina combined, and nearly three times as many people have already voted early in California alone as voted in all four early states.

“There are a bunch of candidates who need to ask themselves why they’re in this race,” said Lilly Adams, a former top aide to Kamala Harris’ presidential campaign. “Are they in it today to be introduced as a presidential candidate at events or are they in it to win? If they are the former not the latter then they should get out.”

Joe Biden’s campaign is “very much alive” again, as the candidate himself put it on Saturday night after a crucial win in South Carolina, but he has precious little time to catch up to Bernie Sanders.

Sander’ campaign has already been running TV ads in 12 of the 14 March 3 Super Tuesday states and announced Sunday that it’s now going on air in nine more states that vote on either March 10 or March 17, fueled by a strong $46 million fundraising haul in February.

Then there’s former New York City Mayor Mike Bloomberg, who will appear on the ballot for the first time on Tuesday after spending more than half a billion dollars, mostly on TV ads in dozens of states.

“Biden’s momentum is about to run into Bloomberg’s money — will they cancel each other out?” asked Addisu Demissie, who managed California Gov. Gavin Newsom’s 2018 campaign before running Cory Booker’s now-abandoned presidential run.

Let our news meet your inbox. The news and stories that matters, delivered weekday mornings.

Momentum has proven to be a fickle master so far this year.

Sanders had plenty of it heading into South Carolina and Joe Biden had none, but Biden was the one who won big. Pete Buttigieg’s surprise wins in Iowa and a second-place finish in New Hampshire did little for him in later contests, nor did Amy Klobuchar’s shock third-place finish in New Hampshire.

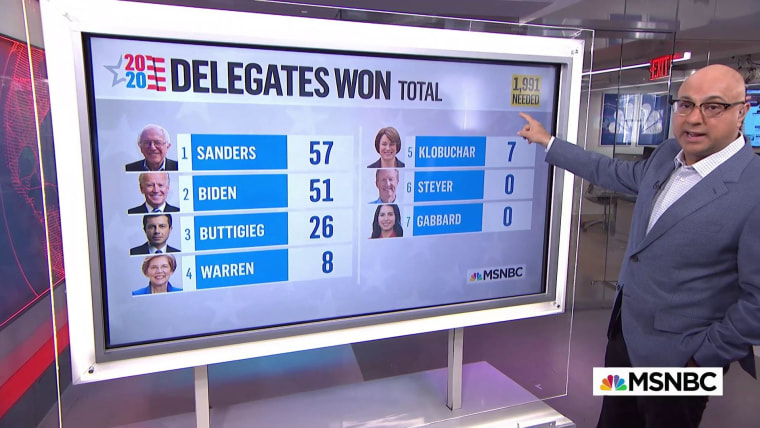

Polling of Super Tuesday states suggest a potentially split outcome, with Sanders in the strongest position, followed by Biden and Bloomberg, but there’s potential for other candidates to notch their own victories, too.

“Everyone keeps assuming that the more people vote, the better chance we have of figuring this all out, but what if the picture only gets more muddled with more voting?” asked Rebecca Katz, a progressive Democratic strategist.

It won’t so much matter who wins states as who earns delegates, since the two are not always linked.

For instance, Buttigieg and Elizabeth Warren may not win a single state Tuesday, but could nonetheless walk away with a sizable delegate haul.

If polls prove correct, Warren is on track to be the only candidate other than Sanders to win any statewide delegates in Massachusetts and California, since the rest of the field is below the 15 percent threshold needed to qualify for delegates.

Buttigieg, meanwhile, is hoping to surpass that threshold in the largest number of congressional districts, which award roughly two-thirds of all delegates while statewide results award the other third.

One problem for Warren and anyone hoping for California to provide some clarity in the face is that the state is notoriously slow to count its ballots. It accepts mail-in ballots up to three days after election day and gives county elections officials 30 day to count them.

“In California we prioritize the right to vote and election security over rushing the vote count,” Secretary of State Alex Padilla said in a statement.

Klobuchar’s Minnesota and Warren’s Massachusetts both vote Tuesday — and polls suggest Sanders could win both, which could make things awkward for them.

But Warren’s campaign manager, Roger Lau, said in a memo to supporters on Sunday that his team expects “no candidate will likely have a path to the majority of delegates needed to win an outright claim to the Democratic nomination.”

That means they expect the contest to be decided at the Democratic National Convention this summer, where the party could potentially pick someone other than the delegate-leader as its nominee.

“Our grassroots campaign is built to compete in every state and territory and ultimately prevail at the national convention in Milwaukee,” Lau said.

And Warren’s team is hardly alone in that assessment, which could lead to several candidates arguing they have a place in the race, even if they don’t have a clear path to the 1,991 delegates needed to clinch the nomination.

“I’m feeling some strong ‘Back to the Future’ vibes,” said Rob Friedlander, a former top aide to Beto O’Rourke’s failed presidential campaign, paraphrasing a famous line from the movie: “Where we’re going, we don’t need paths.”