In February, Kristina Jameson moved into one side of a double shotgun home in Treme, a historically black neighborhood of New Orleans, paying $875 a month in rent, including utilities. She had a day job at a cafe in the Seventh Ward that she loved and a side gig as a community organizer.

But the coronavirus outbreak has upended her life: She filed for unemployment Monday and realized she’ll collect about $64 a week while subsisting on her small amount of savings.

On Wednesday, her real estate management company, MetroWide Apartments, sent her and other tenants a letter warning that the rent is still due on the first of the month, that late fees will still be applied if they are delinquent and that evictions will continue.

“No heart. No understanding,” Jameson, 29, said of MetroWide, adding that it took more than a week for proper utilities to be hooked up after she moved in. “And that’s how it’s been.”

After NBC News reached out for a response, MetroWide landlord Joshua Bruno said in an email that the contents of the initial letter to tenants were not what was intended and should have included community “resources for residents that may need temporary assistance.” The company, which has legally tangled with the city in the past to the detriment of renters, is still urging tenants to pay on time.

“We sincerely apologize for any misunderstandings and unauthorized notice sent,” management wrote.

Still, Jameson’s living situation remains fraught, and she stands with a countless number of tenants and homeowners nationwide who are walking financial tightropes when it comes to their economic security during the global pandemic. With the national unemployment rate potentially rising to 20 percent and high traffic crashing some states’ unemployment benefits websites, the threat of soaring evictions across the country is real, housing advocates and researchers say.

Full coverage of the coronavirus outbreak

If city, state and federal governments don’t step in now, they warn, at stake are people’s homes and health if they’re evicted and thrown out onto the street, which would only exacerbate a deepening public health crisis.

“We’re in an unprecedented historic position,” said Alieza Durana, a writer and spokeswoman for the Eviction Lab at Princeton University, which compiles nationwide eviction data. “I think the current moment in history is unique, but it’s also giving us a moment to question what our human rights are and not take for granted: Do we really have to force people out of their homes?”

“We are hopeful that this is a moment that we can come together and look at community-oriented solutions,” she added.

Each year, 3.6 million eviction filings work their way through U.S. courts, according to the Eviction Lab.

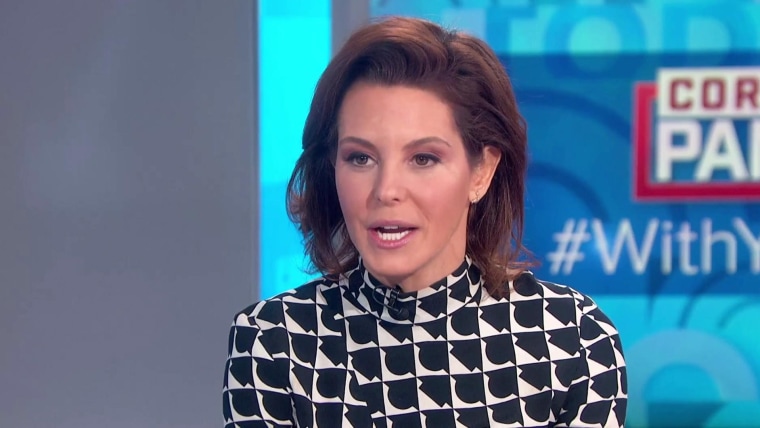

Let our news meet your inbox. The news and stories that matters, delivered weekday mornings.

The pressure on officials now is to create a safety net. New Orleans has joined other major cities and some states that have begun enacting moratoriums on all evictions.

In some places, such as Philadelphia, the moratoriums also cover utility shut-offs, foreclosures and tax liens. While the Philadelphia Housing Authority suspended all evictions for 30 days, Philadelphia’s municipal courts are halting all others for at least two weeks, said the office of City Council member Helen Gym, who helped call for an eviction stay.

San Francisco and San Jose, California, where there are shelter-in-place orders for residents, evictions are being halted for 30 days. North Carolina is also stopping evictions and foreclosure hearings for 30 days.

Boston is going a step further, instituting a moratorium for 90 days with a review every 30 days if needed, while a moratorium is in effect across New York state indefinitely, with housing courts closing except for limited instances in New York City.

Download the NBC News app for full coverage and alerts about the coronavirus outbreak

In New York, it is the most aggressive push yet to protect tenants after partial closings of housing courts became necessary in the wake of the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, and Superstorm Sandy, said Susanna Blankley, the coalition coordinator for the Right to Counsel NYC Coalition, which is made up of tenant organizing groups and advocates.

She added that the city’s housing courts are crammed with thousands of tenants every day looking for relief and that it would be a public health concern to have those people, many of them elderly, waiting to get their cases heard.

Blankley said she’d also like to see rent freezes, particularly for renters who are in the service industry, which is being hammered by layoffs and furloughs because of restaurant and bar closings.

“The last thing we want is for people having to risk their health to save their homes,” she added.

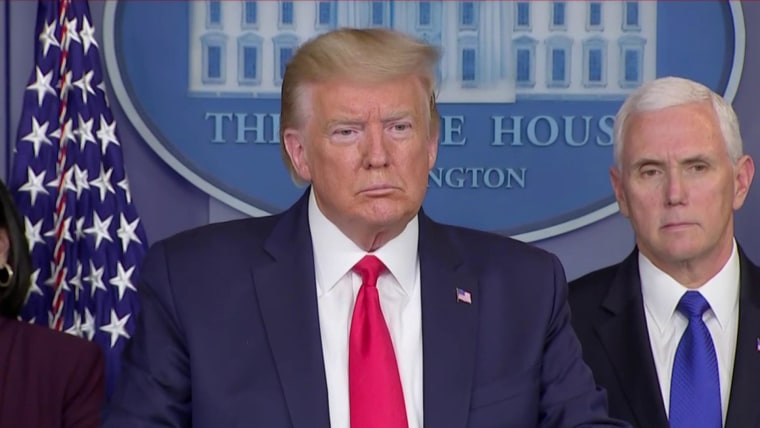

President Donald Trump said Wednesday at a news conference that he was asking Housing Secretary Ben Carson to suspend evictions and foreclosures through April, although the order would apply only to Housing and Urban Development-backed properties.

In Fulton County, Georgia, which includes Atlanta, the chief magistrate judge has suspended eviction hearings for 30 days. The county normally hears tens of thousands of cases a year.

Landlords, however, can still submit electronic filings if they have a case, but tenants are being given an extra 48 hours to respond once the judicial order is lifted, said Ayanna Jones-Lightsy, a staff attorney with the Atlanta Volunteer Lawyers Foundation.

She said she’s most worried about what happens after one month, when people are either still not back on their feet or aren’t getting paychecks right away.

“Atlanta was already in an affordable housing crisis before the pandemic,” Jones-Lightsy said. “As time goes on and rents aren’t paid, landlords are going to want to collect. Their bills are still due. What happens then?”

For the next 30 days, sheriff’s deputies in Cook County, Illinois, which includes Chicago, won’t carry out court-ordered evictions, Sheriff Tom Dart said. Part of the reason, he said, is to protect deputies from coming into contact with people who may have the coronavirus.

Chicago lawyer Michael Griffin, whose firm, Sanford Kahn, files thousands of eviction cases every year, said his landlord clients are being understanding at this time.

“People are in the same boat, and they’re weathering this storm together,” Griffin said. “It’s usually an us-versus-them mentality — not in this case.”

In Philadelphia, where eviction rates as high as 15 percent in some areas disproportionately affect low-income neighborhoods of colors, tenant advocate Barry Thompson said he’s hearing from the city’s working-class renters that they’re bracing for the worst in the coming months. The city has one of the largest income disparities in the country, with some neighborhoods’ median household incomes in the six figures and some as low as $18,722 per household.

“We’re hoping that landlords embrace [a moratorium] with compassion,” Thompson said. “If you’re already struggling today just to make ends meet, you’re going to be thinking down the road, ‘Are they going to take me to court?'”

That’s exactly the nagging feeling that’s already consuming service industry workers across Philadelphia, according to union organizers with UNITE HERE, whose local chapters represent hotel, stadium and airport workers.

“Do we really have to force people out of their homes?”

“It’s a lot of pressure on you, especially when you have kids,” said Robyn Thornton, 35, a mother of one who lost her housekeeping position at a Hilton hotel last week after more than five years on the job. “Whatever you have, you’ve got to exhaust all your resources now.”

With rent for her South Philadelphia apartment at $1,200 a month, she believes she has enough to last her three months.

Michael Scriber, 32, who lives in the Philadelphia suburb of Chester, said he’s going to ask his landlord to help restructure his $600-a-month rent after he lost his concessions job at the Wells Fargo Center, which has been mothballed as sports events and concerts are suspended. The work was steady, and his pay had risen to $15.88 an hour.

Now, he can’t help but think of whether he should take advantage of his local food bank.

“If it’s offered to you, take it,” Scriber said. “Don’t worry about what your pride says.”