Malcolm Kenyatta, a member of the Pennsylvania state House and a supporter of Joe Biden, held up his beverage and smiled. Biden, the front-runner for the Democratic presidential nomination, grinned back, and held up a paper cup, telling his audience that it was filled with Gatorade.

“I’m probably the only Irishman you know who’s never had a drink,” Biden, who abstains from alcohol, said.

It sounds like a classic scene from a campaign meet-and-greet over drinks at a local bar in a battleground state. But this amicable exchange actually happened online during a virtual happy hour, hosted by Biden’s campaign in this new technology-fueled age of socializing — and running for president — in the time of the coronavirus.

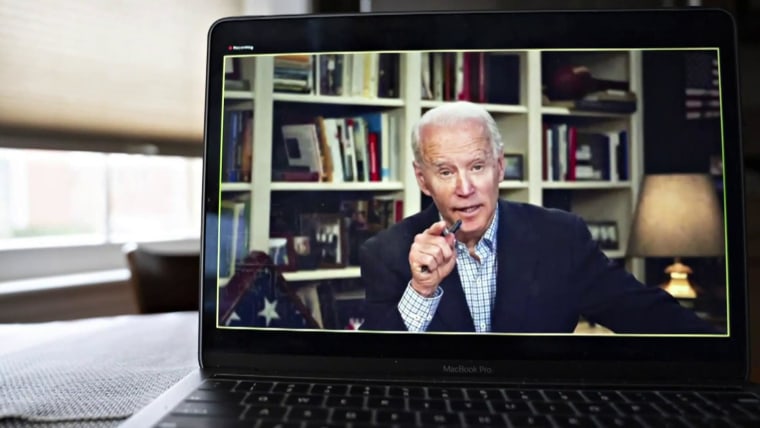

The gathering, which saw more than 310,000 people tune in to the former vice president’s website Wednesday evening, according to the campaign, was mostly glitch-free — and just one of a slew of digital events and TV appearances Biden has added to his schedule in recent days.

But being forced to take his message entirely online has been anything but easy for the likely Democratic nominee, who racked up big primary election wins in early March but largely stayed out of public view as the country confronted a worsening pandemic and his campaign attempted, in fits and starts, to pivot fully to digital. He faced criticism from both the left and the right over seeming to recede into the background at a critical juncture, while renewed efforts to boost his visibility and an improved virtual campaign operation have come as the coronavirus response from President Donald Trump, as well as Democrats like New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, dominates the headlines.

Biden’s campaign acknowledged the steep learning curve it encountered in making the transition — and said it has already seen success with efforts like a digital video explainer on COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus, that it put out to counter Trump’s daily briefings on the topic.

“In the past few days alone, the Vice President has been connecting with millions of people where they are,” campaign spokesperson Remi Yamamoto said in a statement.

Biden, along with Democratic rival Bernie Sanders and Trump, announced earlier this month that, because of the spread of the coronavirus, all of his campaign events will be “virtual,” meaning supporters and members of the media could participate or watch online.

But after two successful events — remarks to supporters broadcast from Philadelphia after his primary night wins March 10 and a speech on the coronavirus delivered two days later from Wilmington, Delaware, and streamed online — issues were apparent. A “virtual town hall,” held via Facebook Live on March 13, was marred by an hourslong delay and significant technical difficulties. (The campaign later emailed reporters vowing to improve the quality of the virtual events.)

The next week, Biden, despite emerging from another round of primaries with a likely insurmountable lead over Sanders in the total delegate count needed to win the Democratic nomination, made even fewer appearances with one livestreamed victory speech and an audio-only call with reporters.

Let our news meet your inbox. The news and stories that matters, delivered weekday mornings.

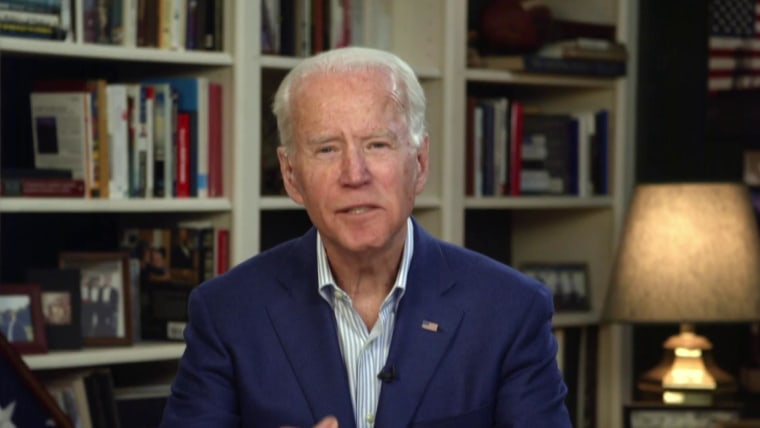

Then, on Monday, Biden made his first video appearance in six days, talking about the coronavirus via a livestream from Wilmington. It marked his debut from a freshly-built studio in the basement of his Wilmington home, which he used in the following days to appear on ABC’s “The View,” and on CNN and MSNBC.

Though Biden’s return to the public eye was a successful one — Monday’s livestream attracted more than 3.5 million views across all platforms, his campaign said — the uptick in appearances revealed new challenges. His Tuesday time on “The View” was interrupted in the New York media market by the daily coronavirus press conference held by Cuomo, whose leadership as the governor of a state hardest-hit by the pandemic so far has attracted national attention and drawn praise from allies and past critics alike.

Hours later, Biden’s interview with MSNBC’s Nicolle Wallace was marred by awkward pauses due to the time it took for each person to hear the other one before being able to respond.

That nearly weeklong stretch of no visual events, meanwhile, prompted criticism from both sides of the political spectrum. The Trump campaign circulated a “#WhereisJoe” hashtag on Twitter, and on the left, left-learning publications and supporters of Sanders seized on Biden’s absence, too.

“Serious question: Where is Joe Biden?” Carmen Yulín Cruz, a national Sanders campaign co-chair and the mayor of San Juan, Puerto Rico, tweeted March 21. Current Affairs, a progressive magazine, published a searing article titled “Where is Joe?” the next day.

David Plouffe, a Democratic political strategist who managed Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign, said on Yahoo News’ “Skullduggery” podcast that the challenges Biden faces are, in part, “just the reality.”

“He’s going to be eclipsed, because, obviously, for good or for bad, and usually bad, we’re in the middle of a crisis and the president is going to take center stage,” Plouffe said on the episode released Wednesday. “You’ve got governors and mayors who are leading crisis response locally. Biden is not in office now, so that’s just the reality.”

But Biden can still break through, Plouffe told the podcast, if he continues to adapt to the digital environment.

“The Biden campaign has an acute need to really up their game and understand how people receive information in this day,” Plouffe said.

Biden himself admitted that there was a learning curve when it came to connecting with his supporters, and to the world, in a virtual campaign.

“What I’m trying to do is become much more facile in being able to use social networking here,” he told Wallace on Tuesday. “The fact is that I’m in the basement of my home.”

“I’m learning how to deal with the vehicles that are available to get news out and get to communicate with people,” he added.

His campaign promised that it would continue to use new tools to meet the moment.

“As we continue in this new campaign environment, we will continue to explore and innovate with new digital tools and formats connecting voters with the vice president and further disseminating his message,” Yamamoto, the campaign spokesperson, said.

Those methods were on full display Wednesday, with Biden holding his first virtual press briefing. Using Zoom, a remote videoconferencing app, Biden spoke for a few moments before his staff called on various reporters to ask questions.

Later, his campaign debuted a new newsletter that included a “What I’m Reading” section, movie recommendations, answers to emails from supporters and a request to donate to the campaign. The email also said that Biden would soon be rolling out a podcast. Biden then appeared on CBS’ “Evening News” program before sipping Gatorade with supporters during the virtual happy hour, initially billed as a “virtual roundtable with young Americans.”

As he listened to a question from Robyn Seniors, the national HBCU Students for Biden co-chair, Biden’s ability to hear his audience cut out.

“I lost my sound, I can’t hear anything, I’m sorry,” he said.

But the snafu only lasted a few seconds before Seniors was able to tell her story about her sister, who like Biden’s son Beau, had developed a brain tumor.

Biden, with a serious look, responded on a personal note — talking about how he was able to persevere through numerous tragedies due to a robust support network and the fact that his family had health insurance.

“I think of all those folks out there who have gone through what I have gone through without any of the kind of help I had,” he said.