More than 60 current and former NFL players and coaches signed their names to a letter to Attorney General William Barr last week asking he use the full force of federal law to investigate the fatal shooting of Ahmaud Arbery, a black man followed and fatally shot by white men in his Georgia community on Feb. 23.

That letter from the Players Coalition, a social justice group formed in 2017 in the wake of player protests during the national anthem, said the Department of Justice and FBI are needed to ensure Arbery’s case wasn’t mishandled by local authorities and that the men charged with murder are held accountable.

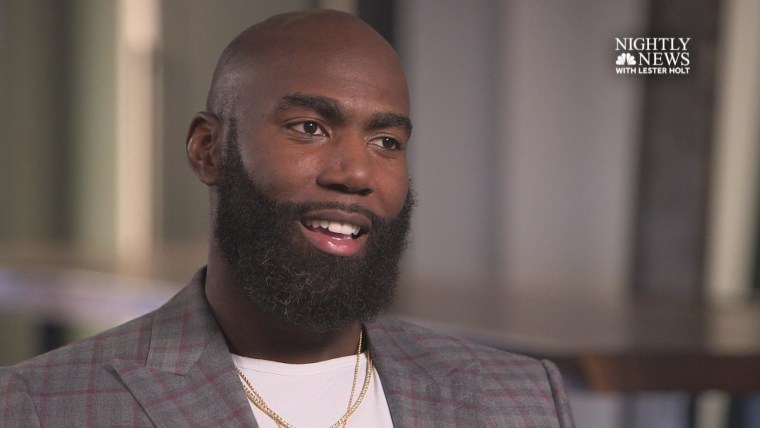

NFL star Malcolm Jenkins, who co-founded the coalition with retired wide receiver Anquan Boldin, told NBC News that the request for federal intervention carries a greater purpose.

“The sad truth is that Ahmaud’s case isn’t unique at all,” Jenkins said. “He is a representation of the ongoing level of distrust that a large part of our communities have in law enforcement and elected officials and the importance of placing reform like-minded people in office who will uphold the highest standards of the law for everyone, regardless of color.”

“It also reinforces that we need hate crime laws in Georgia as well as Arkansas, South Carolina and Wyoming,” Jenkins said of the four states lacking such legislation. “These ‘loopholes’ to justify these kinds of acts will continue to hold us back from justice for everyone.”

Among those who support the Players Coalition’s letter are former NFL player and now-league executive Troy Vincent, Miami Dolphins linebacker Kyle Van Noy, New England Patriots wide receiver Julian Edelman and former Patriot and new Tampa Bay Buccaneers quarterback Tom Brady.

On Friday, Jenkins joined people across the country who jogged for 2.23 miles to remember Arbery.

“Rest in peace, king,” Jenkins, a veteran safety who won two Super Bowl championships, one with the New Orleans Saints and the other with the Philadelphia Eagles and re-signed with the Saints earlier this year, said in an online video. “Doing my jog for you.”

On Monday, the DOJ said it is weighing the possibility of federal hate crime charges, giving Jenkins hope.

The Morning Rundown

Get a head start on the morning’s top stories.

“The FBI and DOJ have an army of resources, and their goal never changes: to protect the vulnerable and intervene where powerful people have caused grave harm,” he said. “They obtained a guilty verdict in the Rodney King case. They held the perpetrators of the Danziger Bridge shootings accountable. They have prosecuted guards at Parchman prisons. And they have led investigations all over the country that have proved critical in restoring trust between law enforcement and people of color.”

Arbrey’s death has resonated with Jenkins and others who say they see themselves in his shoes. He said that as a black man — regardless of his status as a pro athlete — he understands the burden of being scrutinized and the implicit bias of others when he’s out in public.

“Everyday. Walking the dog, taking out the trash, just walking through my own neighborhood, you always must be conscious of what you look like,” he said. “People should not have to worry about the color of their skin or gender to go out for a run in their own neighborhood.”

According to his family, Arbrey, 25, was out for a jog on the February day he was killed, an activity the former high school football player did regularly. White men in a pickup truck with guns chased him in their Georgia neighborhood in Brunswick, a small working-class port city, and told police they suspected him of burglarizing a nearby home.

The Georgia Bureau of Investigation arrested Gregory McMichael, 64, and his son, Travis McMichael, 34, on charges of felony murder and aggravated assault. The men have been jailed since Thursday, and it was unclear if they have a lawyer.

The lag in an arrest — which came more than two months after the incident and following the release of a leaked video of the shooting — frustrated many community members who believe that the McMicheals’ ties with local authorities and racial bias played a role.

Gregory McMichael was a Glynn County police officer in the 1980s and worked as an investigator in the prosecutor’s office in Brunswick until his retirement in May 2019. The prosecutor, Jackie Johnson, had to recuse herself in the case, and then a replacement prosecutor, George Barnhill of the Waycross Judicial District, also stepped aside after Arbery’s family learned that Barnhill’s son had worked alongside Gregory McMichael in Johnson’s office.

The case was transferred to yet another outside prosecutor. Meanwhile, Barnill also wrote a letter in April detailing why he didn’t believe the McMichaels should have been arrested, and that they, along with a third man who recorded the video, had “solid first hand probable cause” to pursue Arbery, a “burglary suspect,” and stop him under Georgia’s citizen’s arrest law.

Georgia Attorney General Chris Carr, who this week asked the Department of Justice to help investigate the case, told NBC News on Monday that part of an investigation needs to determine why those previous district attorneys in the case never told his office that they had conflicts that should have precluded their involvement in the first place. Carr has since appointed a new outside prosecutor — the fourth — to handle the case.

But the earliest a grand jury is expected to be convened is mid-June, when juries in Georgia may resume activity following coronavirus-related restrictions.

Meanwhile, new surveillance videos being reviewed by investigators appear to show Arbery entering a construction site of an unoccupied home on the McMichaels’ block just before he was chased and killed. Attorneys for his family say the videos only show he was “trespassing at most,” and not engaged in other criminal activity.

Jenkins said the video apparently showing Arbery locked in a physical struggle with Travis McMichael was hard to watch.

“Any human being who has seen the video should connect to Ahmaud,” he said. “That said, it is an extremely hard pill to swallow as a black person to watch yet another black body be shot down in the middle of the street. But the most infuriating thing is, as you mourn the loss of a life, is to have their murder justified by white fear and self-defense.”

An autopsy report released Monday shows that Arbery died from two shotgun blasts to the chest and suffered a shotgun graze to his right wrist.

Jenkins said Arbery’s death should be another call to action for people to reexamine the need for citizen’s arrest laws and to hold elected officials and district attorneys accountable for their decisions.

Jenkins, a three-time Pro Bowl safety, has become one of the NFL’s most outspoken players on issues of racial justice. He began using his platform when he formed The Malcolm Jenkins Foundation, a nonprofit charity he started with his mother during his first stint on the Saints’ roster a decade ago. His latest project includes executive producing a documentary called, “Black Boys,” about the black male identity in America.

As for whether this one case would lead to renewed player protests should the NFL jump-start its season later this year, Jenkins said it would be a “disservice” to narrow any activity for a single cause because the larger struggle reaches back far longer.

“The anger and frustration being expressed by professional athletes and people of color all over the country stems from a centuries-long thread of violence against the black body that goes without consequence or justice,” he added. “This has been going on since emancipation.”