In October, Dr. Eve Krief watched from the window of her Long Island, New York, pediatrics practice, as around 20 women gathered on the lawn.

Armed with signs and banners with messages like, “We spread truth not disease,” the women — a group of anti-vaccine activists from New York and California — had come to protest Krief over her recent support for the 2019 state law that removed religious exemptions for vaccines.

Some of the protesters sat with signs, while others stuck anti-vaccine propaganda under car windshield wipers in the parking lot. Several approached parents entering the building with their infants, asking, “Are you vaccinating your baby?”

Krief had experience with these particular women. She recognized the group’s leader, a local mother who had followed her to her car after a community meeting about proposed vaccine legislation a few weeks earlier. Krief said the bill’s passage led to more intense protest from people who had been using the religious exemption to mask their personal preference not to vaccinate. They had also infiltrated her Yelp and Health Grades accounts, posting negative reviews, although they weren’t patients at her practice.

But the in-person protests and the interaction with patients was another level.

“It’s unsettling,” Krief said, adding that her office is beefing up security measures in response.

For the anti-vaccination organizers, Krief’s unease was an indicator of their success.

“Needless to say,” one wrote on her Facebook page, “we rattled her cage just a bit yesterday with our presence.”

New outbreaks and new laws

Opposition to immunizations was once largely limited to online bullying, but now opponents are increasingly taking their harassment tactics into the real world: aggressively following legislators and doctors and, in some cases, using physical violence.

The degree to which the anti-vaccine extremists takes this is in excess of any other group.

But as opposition to vaccination has risen in recent years, so have cases of measles. Major outbreaks occurred in California and New York have spurred lawmakers in those states to strengthen vaccine mandates for school children. Reaction from anti-vaccine groups was swift and violent.

Online conspiracy theorist Austin Bennett livestreamed himself physically shoving the author of California’s law, state Sen. Dr. Richard Pan. Bennett was later charged with a misdemeanor. The next month, Rebecca Dalelio, a participant at a protest at the California state Capitol, was charged with assault and vandalism when police say she threw a menstrual cup full of blood on lawmakers in the gallery.

Pan, who is also a pediatrician, suspects he was Dalelio’s target.

“Everyone around me was hit” when the blood splattered on the legislative floor, he said.

Pan said anti-vaccine groups have stalked him at conferences, speaking engagements, even the March for Science in Washington.

As legislators, “we deal with all sorts of contentious issues — guns, abortions, lots of issues people are very passionate about,” Pan said. “But the degree to which the anti-vaccine extremists takes this is in excess of any other group.”

“An awful new normal”

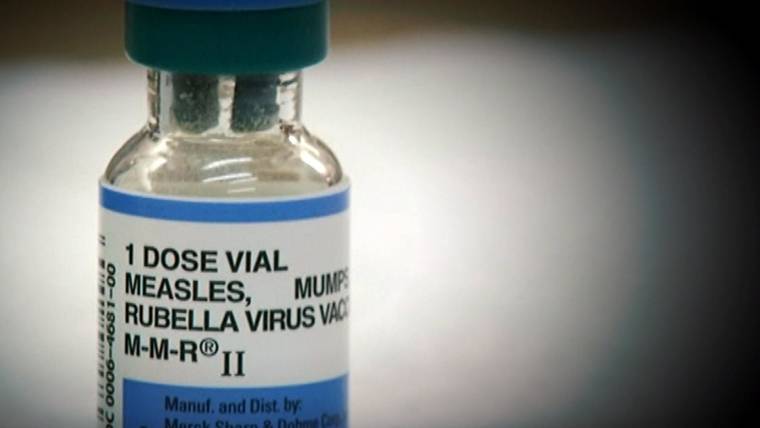

The main target of the anti-vaccine community is the MMR vaccine, which protects against measles, mumps and rubella. False links between the vaccine and a variety of conditions, including autism and sudden infant death syndrome, have been widely circulated on social media. These alleged links have been fully debunked.

On Thursday, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that overall, there’s been a 66 percent drop in measles cases worldwide since 2000, largely thanks to vaccination. The report estimates 23.2 million lives have been saved around the world because of the MMR vaccine.

Let our news meet your inbox. The news and stories that matters, delivered weekday mornings.

But the downward trend of measles cases is showing worrisome signs of reversal. In the United States this year, 1,261 measles cases have been reported in 31 states — the largest number in almost three decades, according to the CDC.

During an infectious diseases conference in New York in November, Dr. Peter Hotez was followed throughout a hotel by several aggressive anti-vaccination protesters who filmed while pelting him with questions predicated on vaccine hoaxes. Hotez is a vaccine scientist, dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at the Baylor College of Medicine, and author of the recent book, “Vaccines Did Not Cause Rachel’s Autism.”

Hotez tweeted from the event, thanking hotel security for “getting me out safe.”

“I’ve been targeted by them for 20 years,” Hotez said. But the real-life harassment is part of “an awful new normal.”

For years, people opposed to vaccines have flooded Hotez’s social media accounts, calling him a shill for the pharmaceutical industry, though he’s never been paid by a drugmaker. That harassment has increased as the anti-vaccination movement has grown, first on social media, and then assisted by the sale of books and videos through Amazon, Hotez said.

The handful of doctors and scientists targeted by the movement have been largely left to combat misinformation and weather the subsequent harassment on their own, he added.

The CDC, the surgeon general and, until recently, even major medical societies and doctors, have been slow to counteract misinformation spread by vaccine protesters, Hotez said. That unwillingness to engage the anti-vaccination crowd could have disastrous consequences, he said.

“Future measles outbreaks, deaths from the flu,” Hotez said. “We’re condemning a generation of women to cancer,” he said, referring to the HPV vaccine, which protects against cervical cancer, as well as cancers of the anus, penis and throat.

At the center of these aggressive protests and actions is Joshua Coleman, who claims a vaccine injury confined his son to a wheelchair. Coleman — who was charged with willful cruelty to a child in 2015 related to a fight over a parking spot at a local elementary school — organizes events like the one that targeted Hotez, and provides templates for the black and red signs emblazoned with vaccine misinformation that have been a staple of recent protests.

Vaccine advocates have likened the newer protests to publicity stunts from the Westboro Baptist church — offensive signs and sometimes costumes, paired with harassment of passers-by at events the media is already covering. Events in Times Square, at Disneyland, and at the premiere of the movie Frozen II, which stars the actress Kristin Bell, an outspoken supporter of vaccinations, have been counted as successes and shared widely by the anti-vaccine community on their Facebook and Instagram pages. Bell is a favorite target; activists recently crashed the unveiling of her star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame and interrupted her appearance on The Jimmy Kimmel show.

Going offline

The real-world attacks on doctors, scientists and vaccine supporters seem to be a direct response to this year’s actions by Facebook and YouTube to rein in vaccine misinformation on their platforms. Videos and posts with content the platforms label as vaccine misinformation aren’t being seen and shared like they were in 2016.

“’I’m not able to communicate online through videos anymore and actually have people see it,” Coleman said. “That’s kind of what started the whole concept of taking it to the streets and being out there with signs and with flyers.”

The threat of in-person violence has always been there.

Coleman travels extensively; in November, he was in New York, California and Hawaii. That travel is supported by people who donate their airline miles, take up collections, or provide free lodging, in exchange for his help planning and documenting their protests, Coleman said.

He dismisses claims of harassment.

“These guys are making a big deal out of nothing,” Coleman said.

When presented with examples, such as the woman who threw blood at Sen. Pan, Coleman distanced both himself and the greater movement. “I’m just as horrified as anybody else,” he said. “It really isn’t indicative of the behavior of most of our people.”

Indeed, Coleman and other prominent anti-vaccine groups says the perpetrators were not associated with the larger movement.

But Coleman’s signs were on display outside a Thanksgiving turkey drive at a school in Sen. Pan’s district where flu shots were being administered to low-income residents. One activist livestreamed on Facebook from inside the school gymnasium. In the video, she mocks Pan and his aide, while telling parents attending the drive that vaccines cause harm.

A chilling effect

The continued harassment could have a chilling effect among public health advocates and parents, said Leah Russin, executive director of the parent advocacy group, Vaccinate California.

“The threat of in-person violence has always been there,” Russin said. “But I think the reality of it has escalated. My fear is that it’s going to drown out and shut down public health advocates.”

The anti-vaccine vitriol has proven effective in Florida.

State Sen. Lauren Book filed a bill that would have removed the religious exemption for vaccinating school children in the state. Anti-vaccination parents and groups soon filled public hearings, insisting that legislators reject the measure.

Book was also the target of a social media smear campaign filled with profanity from anti-vaccine groups, as well as images of Book mocked up to look like Adolf Hitler. Book is Jewish.

The legislature declined to hear debate on the bill, rendering it dead on arrival.

“I knew this was a very serious group of folks, but I don’t know that I knew the voracity with which they advocate,” Book said. “There is no conversation. There is no common ground.”

“It’s been a very, very difficult road,” she added.

Both Pan and Book say they want to have a dialogue with people who have earnest questions or concerns about bills, but draw the line at violence.

“If we make policy based on conspiracy theories, that’s not good for our country. That’s not good for society. Policy needs to be grounded in truth,” Pan said. “We need to be clear: bullying and intimidation of this kind is unacceptable.”

Krief, the Long Island pediatrician, said that getting patients to vaccinate and discussing parents’ questions is her “biggest responsibility.”

“We’ve saved millions of children’s lives because of vaccination. But we live in an age where people haven’t seen the harm and death that these diseases caused in the past,” she said.

“Because they haven’t lived it, they don’t understand.”

Follow NBC HEALTH on Twitter & Facebook.