Most climate scientists will be quick to say that 2019 was the year that Greta Thunberg truly became a force to be reckoned with.

The 16-year-old Swedish activist staged solo “Fridays for Future” school strikes that triggered a global phenomenon drawing millions of people into the streets to protest climate inaction. The teen has since become the face of that newly energized climate movement and was recently named Time magazine’s Person of the Year.

“She represents the best of humanity,” said Benjamin Houlton, a professor of global environmental studies at the University of California, Davis. “She frightens those in power right now because she has a very clear message and she’ll continue to be an important crusader.”

But while Thunberg’s influence soared and climate change permeated the cultural psyche, it was also a year in which the strong public engagement and the changing rhetoric surrounding climate change were not matched by aggressive policies to tackle global warming.

“We’re completely divided everywhere,” said Anders Levermann, a climate scientist at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany. “One side is getting very loud and demanding change, but the other side is saying climate change isn’t happening or isn’t man-made or is too complicated to change. That is like looking at a world of slavery and saying it’s too complicated to change. I think there’s a pretty clear right side of history and wrong side of history.”

Levermann worries that malevolent forces are preventing humanity from taking the right side.

“There’s a much bigger problem than climate science denial — it’s fact denial,” he said. “Science is about truth, but if you can’t agree on facts, then the most powerful man in the room can decide what is right and wrong.”

Still, he sees some glimmers of hope. Though President Donald Trump announced in 2017 that he intends to withdraw the United States from the Paris Agreement, a climate accord ratified by 187 countries that aims to sharply reduce carbon emissions, the response elsewhere has not been apathetic.

Earlier this month, the European Union unveiled a plan for its 28 member nations to become “climate neutral” by 2050 by eliminating their contributions to climate change. The proposal, known as the European Green Deal, was heralded as one of the most ambitious plans introduced by any government so far.

“It’s only a plan at the moment, but it is a plan,” Levermann said. “A carbon-free continent by 2050 is precisely what is needed for the world, and if we can manage it in a highly developed place that is one of the biggest economic engines on the planet, then it would send a very strong signal.”

Let our news meet your inbox. The news and stories that matters, delivered weekday mornings.

China is also starting to invest heavily in renewable energy, a shift away from fossil fuels that could become a trend across other economies and industries.

“In a sense, we’re at a tipping point for world industries, but the hope is that we’re tipping in the right direction and not back to the Stone Age,” Levermann said.

Carly McLachlan, a researcher at the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research in the United Kingdom, said she has noticed a significant change in the public’s acceptance of climate science — and the urgency needed to stop global warming.

“In 2019, it became quite common to frame climate change in the language of an emergency,” she said. “We moved away from the sense that we need incremental change, and the language we’re using shows this is really a defining issue.”

Yet despite growing public recognition of the urgent need for action, this year saw attacks on climate science from the governments of several countries, such as Brazil, the United States and Australia.

At a United Nations climate summit in early December, countries failed to agree on certain core issues of the Paris Agreement, and several countries including Brazil, Saudi Arabia and Australia were accused of thwarting the negotiations.

But Houlton, of UC Davis, thinks the realities of climate change will become harder to ignore as carbon emissions continue to rise and communities around the world face warming temperatures, rising seas and more intense episodes of extreme weather.

This year was the fourth consecutive Atlantic hurricane season with above-average activity, Europe sweltered through a historic heat wave in June and dry conditions fueled massive bushfires that are still raging across Australia and have already scorched an area equivalent in size to the state of New Jersey.

Scientists say these extreme events are likely linked to climate change and will become hallmarks of the “new normal” for the planet.

“Climate change is not about how we’re going to become extinct in 10 years or 20 years,” Houlton said. “It’s about: How much suffering do we want on the planet? How many people have to die or move their homes? How much economic disruption do we want?”

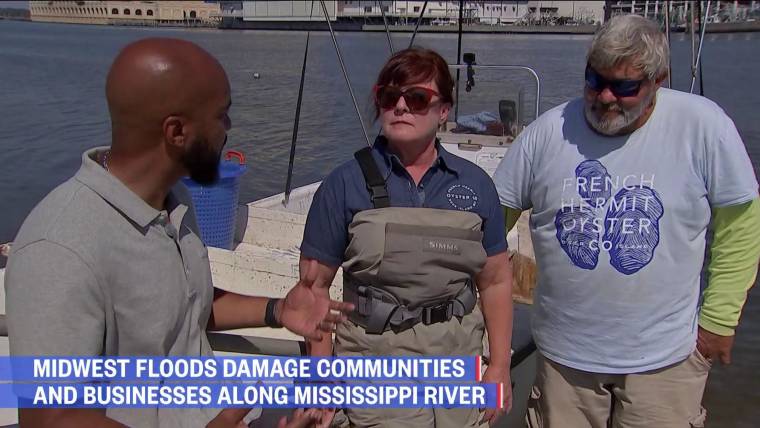

In the U.S., the disruptions have been apparent, according to Joanna Lewis, an associate professor of energy and environment at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. Parts of the Midwest and the South saw record flooding this year and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration recorded weather and climate disasters in 2019 that each cost more than $1 billion.

“It’s becoming more clear to people that climate change is not something that is a long way off — it’s something affecting people today,” Lewis said.

But while the effects of rising seas and extreme weather may play out at the local level, tackling climate change will require international cooperation.

“If I go out for a run, I will start to lose weight, but if I cut emissions, I may not see that benefit play out in my community but it might help somebody out in another community,” Houlton said. “We have not evolved to deal with that idea of interconnectedness between people, places and economies. We can’t compartmentalize. We need a complete societal transformation.”

Laurence Smith, a professor of earth, environmental and planetary sciences at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, said this year was characterized by a shift away from debates about the science of climate change to discussions about policies and solutions.

“We know the science is real, so scientific work is taking a back seat to political will, which is what we really need now,” Smith said. “A lot of great things are happening at the local level, spearheaded by cities and states, but that’s not enough. There needs to be some top-down policy as well.”

Smith thinks the demand for political action in the U.S. and elsewhere will be largely driven by young people, like Thunberg, who see climate action as a priority. Thunberg’s activism has inspired youth-driven movements around the world that culminated in a Global Climate Strike in September that saw more than 4 million people worldwide participate in organized climate protests.

“I haven’t seen this level of engagement before,” he said. “It’s beginning to really matter with young people, even though it’s unfair to kick this off to the younger generation and say: You guys fix it. So I’m pleased that young people are engaged, but it’s also sad.”

For Levermann, the incremental progress made in Europe and his home country of Germany gives him reason to be optimistic. And he recognizes that big changes to societies, economies and industries require some patience.

“Solving climate change is a huge endeavor, and it requires the whole planet, and the democratic process is slow,” Levermann said. “I’ve seen a lot of motion, but we are far from having solved this. This will be a struggle until the end of my life but, hopefully then, I can say to my children: ‘Here you go. We did this and now you have to solve the next one.’”