Mike Bloomberg served as the mayor of New York City from 2002 to 2014. Now he’s running for president of the United States, once again using his wealth and privilege to enter the race late, skip the rigor and scrutiny of town halls and debates, and buy his way up in the polls. As Democrats scramble to understand his record, his stances on the issues, and the value system that drives his decision making, I want to tell you about my experience as a black man in Mayor Bloomberg’s New York.

The hallmarks of Bloomberg’s tenure were economic displacement and the school-to-prison pipeline, with the key pillar being his stop-and-frisk policies, where police disproportionately stopped black and Latino men to check for weapons. As a working-class black male educator during the entirety of Bloomberg’s tenure, I got to experience the horrors and the trauma of how his police department treated people like me. Here are just two examples of many.

When you are locked in a cage, you are suddenly no longer human. You’re an animal. Your spirit shifts into survival mode.

In 2004, I was driving home from my teaching job at an elementary school in the South Bronx, on my way to pick up my 3-year-old son and wind down for the evening. I saw sirens flashing in my rearview mirror. This was not the first time I’d been pulled over by the cops, nor would it be my last. It is something one never gets used to, and every time it happens your heart skips a beat. You feel guilty even though you didn’t do anything wrong.

I remember the officers approaching the vehicle and telling me I hadn’t properly used a turn signal, and I remember them taking my license and insurance. I waited for what seemed like forever with increasing anxiety in every moment. When the cops returned, they asked me to step out of the car, turn around and put my hands behind my back. I don’t remember asking why or if they just told me that my insurance was suspended. I knew this wasn’t true, but I didn’t dare open my mouth. I was well aware of what might happen if you talk back to the cops from Rodney King’s beating by the L.A. police. So I kept my mouth shut.

Get the think newsletter.

I was taken to the local police precinct and put in a cage not much bigger than a bathroom, with two other people, one bench and one toilet. While one person gets to occupy the bench, the other two are forced onto the filthy floor. When you are locked in a cage, you are suddenly no longer human. You’re an animal. Your spirit shifts into survival mode.

I spent what must have been a few hours in one cell before being transferred via paddy wagon to another cell. I was handcuffed and placed in the back of a dark van behind a cage. It’s a terrifying experience. You lose your bearing because you don’t quite know where you are or where you’re going.

After spending another few hours in the second cell, I was released without seeing a judge. No explanation. No apology. No car either, as it was impounded. I had to borrow money just to get it back the next day. I was grateful to be free and get home to my son and my mother, who was watching him. We didn’t speak much about the incident because I was just happy to be home.

The year before, I was arrested and accused of stealing my own car because I parked somewhere illegally. That time my son was with me, as was my friend. My son got to see his daddy arrested by the police. Once again, I recall being detained for hours before being released without charge.

Contacted now about these events from over a decade ago, the New York Police Department wasn’t able to offer a response about the cases because I couldn’t provide a specific date or location for these events. But the lack of paperwork, since I wasn’t ever charged with a crime, underscores the problem. And while I no longer remember the exact date of the incident, the memory of it has lasted for years, reinforced each time I’ve retold the stories.

Of course, my experiences are nothing compared to what Kalief Browder went through before taking his own life. Or what the families of the 42nd precinct in the Bronx had to deal with. Or those of Eric Garner, or of Sean Bell.

Bloomberg’s assault on black lives didn’t just occur in black neighborhoods. It also occurred within our public school system. While our communities were occupied by police, our schools were occupied by school safety agents. As Bloomberg said in the New York Post, “If I have to put a police officer next to every kid, we’ll do it.” The school safety agent task force would’ve been considered the 10th-largest police force in the country during Bloomberg’s tenure.

Bloomberg had no problem sending teams of cops into our schools to discipline and control black and brown kids. Instead of hiring more teachers, guidance counselors and social workers in the public schools attended by other people’s kids, he instituted metal detectors and more safety agents, pushing more black and brown students into the school-to-prison pipeline. Eighty-two percent of students attending high schools with metal detectors were black or Latinx, and these schools were academically underfunded by almost $2,000 per student.

Bloomberg’s assault on black lives didn’t just occur in black neighborhoods. It also occurred within our public school system.

At the height of his mayoralty, nearly 75,000 children were suspended from school. The majority of them were black boys, and some 10,000 of these children were suspended for simple insubordination. By comparison, New York City schools suspended around 30,000 children a year post-Bloomberg.

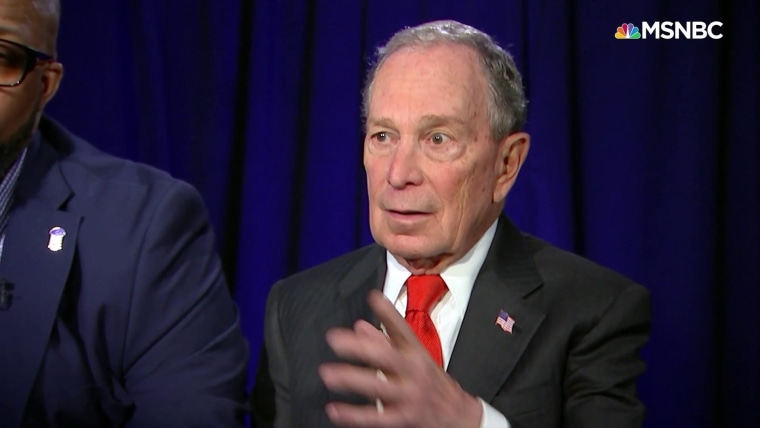

So now Mike Bloomberg is running for president, and he seems to believe that an apology for his stop-and-frisk policy is enough to erase the trauma and the pain he caused the black community in New York City. It’s not.

The bottom line is that Bloomberg either consciously allowed himself to embrace racist values, or he is unaware that he has inflicted them and lacks the self-awareness to truly reckon with his past and repair what he has harmed. He has not done either, which makes him unfit to be president.