After a long day at the office, Hannah Johnson, a deputy county prosecutor in Indiana, likes to unwind with a movie — so she throws one of the nearly 200 VHS tapes she owns into her VCR player.

“It’s a comfort thing, especially if I’ve had a stressful day at work. VHS allows me to go back to being a kid. I don’t have to worry about work or politics,” said Johnson, 24, who also subscribes to several streaming services. “I know everything on Disney Plus is digitally remastered, but compared to VHS, it just doesn’t feel authentic.”

Johnson, who started scooping up Disney and “Harry Potter” cassettes for 50 cents a pop at used bookstores in college, is part of a quietly thriving subculture of VHS enthusiasts: collectors, traders and design obsessives across the U.S. who adore the defunct video format.

VHS has long been out of mainstream fashion. Hollywood studios stopped releasing movies on tape nearly 15 years ago. Netflix, Amazon Prime Video and WiFi-powered digital behemoths now dominate the home video market with sprawling libraries and crystal-clear picture quality.

But for passionate hobbyists, indie retailers, media experts and average film-watchers who spoke to NBC News, VHS will never go out of style. They find nostalgic charm (and, in some cases, financial value) in hunks of plastic that some might consider useless junk.

“We watch these tapes and it’s like getting a window into the past. It’s about simplicity, not quality,” said Sarah Godlin, 39, a copywriter in the admissions office at California’s Humboldt State University who picks up tapes at local thrift stores.

Instagram, in particular, is home to some of the most creative expressions of VHS ardor. Aficionados post photos of their collections organized by color (hashtag: #vhscollectorsunite); graphic designers upload images from contemporary movies reimagined as retro VHS box art.

The tape trade

At least a few major retailers are taking notice — and capitalizing. Target, which no longer offers VHS tapes in stores or online, sells editions of “Jaws,” “The Breakfast Club” and the second season of “Stranger Things” in chunky VHS boxes with fake scuff marks. Disney hawks wearable pins shaped like clamshell cases from the 1990s.

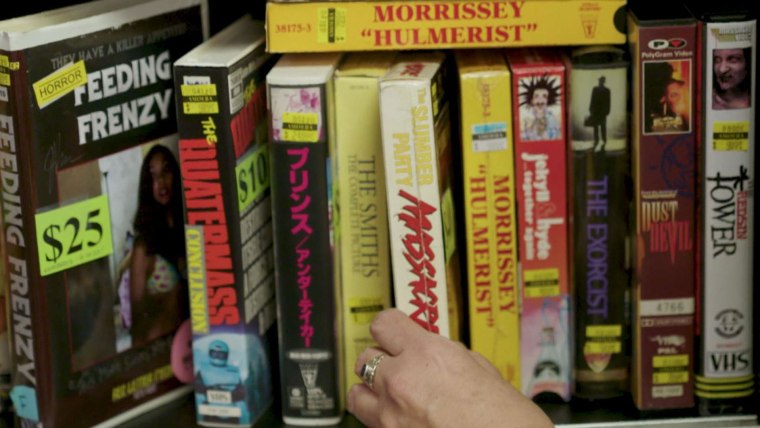

Meanwhile, record shops and secondhand stores are awash in tapes. EBay spits out more than 600,000 results if you search “VHS movies.” Amazon Marketplace features tens of thousands of listings.

Jackie Greed, who works at the indie record emporium Amoeba Music in Los Angeles, used to struggle to find takers for the store’s trove of used cassettes, wondering if she’d ever be able to sell the stuff.

But in the last few years, the tapes have been “selling faster than I can keep up with,” Greed said, adding that 20- and 30-something customers are burning through everything from megahits like “Titanic” to relatively run-of-the-mill titles from the 1990s, such as the Clint Eastwood thriller “Absolute Power.”

Let our news meet your inbox. The news and stories that matters, delivered weekday mornings.

Greed, 51, said that these days Amoeba Music sells close to an average of 2,000 VHS tapes every month. (She and her boyfriend have more than 5,000 tapes in their personal collection.)

The renewed enthusiasm for the old format has created a small but spirited cottage industry.

Adam Haug, a graphic designer and veritable VHS addict who lives in Omaha, Nebraska, said he has “amassed hundreds of friends in the VHS community,” a patchwork of folks who assemble in private Facebook groups and Reddit forums, usually with a yen for horror and sci-fi arcana.

“I’m overwhelmed by how big the community has gotten in the last few years. It’s thriving,” said Haug, 38, who said he has “somewhere between 1,000 and 2,000” tapes in his basement, many of them schlocky horror flicks that never made the jump to DVD and then went out of print.

“You’ve got tapes out there that are worth a couple pennies, but there are some worth hundreds of dollars. I love going on treasure hunts at Goodwill, where you can yank something out of the junk bin that’s worth, like, $50 on eBay. I’m almost completely out of room in my basement.”

The big rewind

Caetlin Benson-Allott, a professor of film and media studies at Georgetown, believes this renewed zeal for VHS suggests a hunger for physical media in the digital era — objects you can hold in your hand instead of files floating in the proverbial cloud.

“I think we all had grand dreams for streaming media. You’d get anything you wanted, anytime you wanted it,” Benson-Allott said, pointing out that one of her favorite films — the 1977 Diane Keaton vehicle “Looking for Mr. Goodbar” — has only been available in the U.S. on VHS.

“But we’ve grown increasingly disillusioned. You see the fragmentation of movies on Netflix and HBO GO, and you have some people looking back to older platforms and asking, ‘What did we walk away from there?’ It can be satisfying to have a sense of ownership again,” she said.

Haug, who grew up in the 1980s, agreed that nostalgia — arguably the same backward-looking instinct behind Hollywood’s endless supply of reboots and remakes — was the driving force behind his subculture of choice.

“If you’re a Gen-X kid, you can remember going to Hollywood Video or Blockbuster or a mom-and-pop video shop with your parents. It was such a beloved ritual for so many people, and now collecting gives you a nice flashback to your childhood,” he said.

In some cases, aficionados cherish tapes because they preserve what they consider superior versions of classic movies. The early VHS editions of the original “Star Wars” trilogy, for example, contain scenes that were excised or altered in later director’s cuts and digital releases.

VHS as (low) art

The decidedly lo-fi audiovisual quality of VHS tapes — glitchy freeze-frames, static lines, muffled soundtracks — lures some consumers who have a taste for offbeat art objects, said Dan Herbert, a media scholar at the University of Michigan.

“Interestingly, vinyl records are super mainstream again, and among audiophiles, vinyl is considered high-quality. But with VHS, people are joyfully celebrating low quality,” said Herbert, author of “Videoland: Movie Culture at the American Video Store.”

Haug, the collector in Omaha, said that characterization struck a chord: “You jam the tape in the machine, you hear all that mechanical clicking, you watch these dated previews, you see the fuzzy FBI warning, the picture keeps glitching out. I really dig all that.”

The distinctive aesthetics of VHS — associated for some with the Reagan-era heyday of indoor shopping malls and the Clinton-era economic boom that preceded the 9/11 terror attacks — have bled into experimental pop music, too.

Vaporwave, an internet-driven genre of electronica, is one prominent example: YouTube is filled with videos featuring synth-style “elevator music” played over gaudy neon images that have been degraded to resemble frazzled VHS footage, creating a hallucinatory effect.

VHS tapes were pivotal in at least one absurdist multimedia exhibit, too: Everything is Terrible!, a video art collective, opened a fake store in Los Angeles in 2017 stocked with roughly 14,000 VHS copies of “Jerry Maguire.” (No other tapes were on display.)

But for more casual VHS viewers who may not have the same drive to buy up rare titles or much interest in ironic art projects, the now-antique format offers simple, low-stress comforts that are increasingly scarce on the internet — or in the real world.

Godlin, the university copywriter, said she likes setting her kids in front of a VCR because, unlike their hours online, she has full control over what they watch. She lives in an area where electricity frequently cuts out, so a VCR player powered by a small generator comes in handy.

Johnson, the county prosecutor, also savors the VCR as one of the few video platforms that isn’t WiFi-connected. But there’s one part of the VHS experience she finds frustrating — a basic limitation familiar to anyone old enough to remember the world before iTunes.

“You have to rewind. If you forget to rewind, you pop the movie in and it starts at the end credits and you’re like, ‘Gosh darn it!’ It drives me crazy,” Johnson said. “I’ve gotten a little spoiled by the internet, I guess.”