To determine how much the schools charge each individual student, NBC News had to contact each public Division 1 university. Eight declined to disclose the exact amount they bill each student, despite repeated requests.

More than half of public Division I schools assessed an annual athletic fee of at least $100, and the price at several exceeded $2,000. The highest confirmed by NBC News was $3,340, charged by the Virginia Military Institute. Next was the Citadel in South Carolina, which charged $2,713.

These student fees covered far more than just athletic scholarships. Expenses for coaches and administrator salaries account for almost twice what is spent for scholarships in Division 1 sports.

There were 43 public universities that reported not charging fees for their sports programs, including perennial football powerhouse the University of Alabama and the University of Texas in Austin.

Others rely heavily on student fees. At least one school used its fees to keep itself from being kicked out of the top tier of Division 1.

Miami University in Oxford, Ohio — which charged students $1,044.87 in athletic fees this school year — has used money from student fees to make up for low ticket sales. It purchased 10,000 of its own football tickets per home game this past season. The tickets were not resold at a discounted rate or donated.

The NCAA requires the universities playing in Division 1’s top tier, a more competitive collection of 130 schools known as the Football Bowl Subdivision, to maintain an average paid attendance of 15,000 at home games.

“Because Miami does not average 15,000 in actual attendance, Miami uses a portion of the student fee” to buy football tickets, said Claire Wagner, a spokesperson for the school.

The price of transparency

Let our news meet your inbox. The news and stories that matters, delivered weekday mornings.

Students often have little way to know how much they’re paying towards athletics. Many schools, despite reporting large revenues from student fees in athletic finance documents, do not list an athletic fee on their website or tuition bills.

NBC News examined actual tuition bills received by students from 20 schools in six states that collect athletic fees, and didn’t find the fees listed on any of the bills. In more than half of those cases, we were able to determine the fees by looking at a school’s financial website. In the rest, however, we had to ask a school official or file a public records request.

When Waltemyer receives her tuition bill from James Madison, it does not list a specific athletics fee. She had to look online for documents from the school’s financial office to learn that she is charged a fee to fund sports teams.

Students at Ball State University in Indiana get even less information. The school does not reveal the fee online or in tuition bills. The school collected $13.3 million in student fees for sports teams during the 2017-2018 academic year. A rough estimate, based on undergraduate enrollment, would mean the school charged $879 for each student. Andrew Zimbalist, an economics professor at Smith College, said that calculation would be a fair gauge, though not a precise one, of the burden that students face. The university declined to disclose its exact student fee.

Ironically, most of the schools with the highest per-student athletic fees on our list have high fees because they are more transparent than other schools about how they spend money on athletics.

Twenty-five of the 30 schools with the highest per student fees on our list are from just five states. Virginia alone accounted for seven of the top 10. That’s because public universities in Virginia, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina and Ohio adhere to some form of an accounting rule recommended by the National Association of College Business Officers (NACUBO).

NACUBO defines the “auxiliary enterprises” of a school as financially self-supporting divisions that do not receive state funding — such as dining programs or residence halls.

Some states or individual schools choose to treat Division 1 athletics as auxiliary enterprises, therefore restricting state funding to athletic programs. In practice, it means costs wind up charged directly to students.

In some states, like Virginia, Maryland, and North Carolina, versions of NACUBO’s accounting recommendation are enshrined in state policy. In other states, like South Carolina and Ohio, schools have more latitude but still try to adhere to the NACUBO rule.

In Virginia, a spokesperson for the State Council of Higher Education said that the agency actively enforces the rule and does not allow Division 1 athletic departments to receive state funding.

A spokesperson from the Ohio Department of Education said there was no legislation in the state that relates to athletic funding and all decisions as to fees are made by the individual institutions.

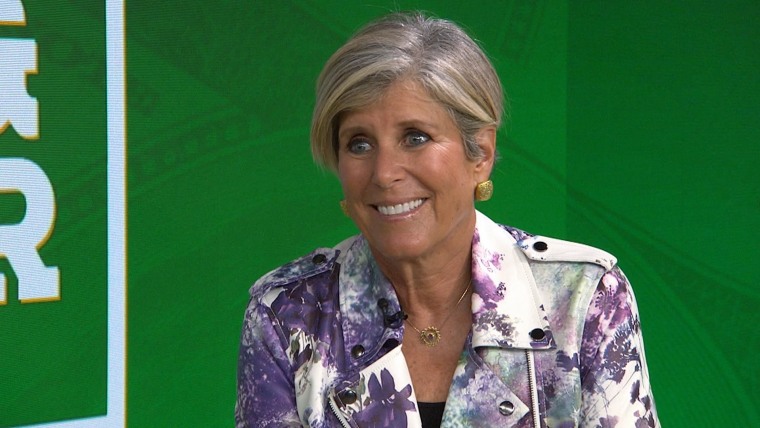

Sue Menditto, a senior director of accounting policy at NACUBO, said it is up to the states whether or not they want to enact the rule into law or how rigorously they want to enforce it.

“It really depends on the relationship between the public institution and the state,” Menditto said. “It’s also the state’s budget and their philosophy towards athletics.”

Lower fees? Not really

State schools that don’t follow the NACUBO rule have lower reported athletic fees. However, that doesn’t necessarily mean students are paying less for sports.

The NCAA does not require universities to report whether tuition is used for sports teams. Instead it only asks in broader terms whether athletics gets funding through a combination of tuition payments, state grants, endowments and other income.

That means students may be financing programs indirectly, with fees bundled into tuition or other general costs. Many institutions reported that, while they did not receive revenue from student fees, their athletic department was funded through the larger mixture of tuition, state grants, and endowments.

Robert Kelchen, a Seton Hall University professor who examines higher education finances, said that schools that don’t follow the NACUBO rule likely divert some tuition revenue toward athletics if they are allowed. “State funding is often restricted to be used for educational purposes,” said Kelchen, “and many public institutions get much of their remaining available revenue from tuition.”

“The big issue is that students end up footing much of the bill for athletics,” said Kelchen. “And in many cases students have little to no control over the fees they end up paying.”

The lack of transparency upsets advocates trying to combat rising school costs.

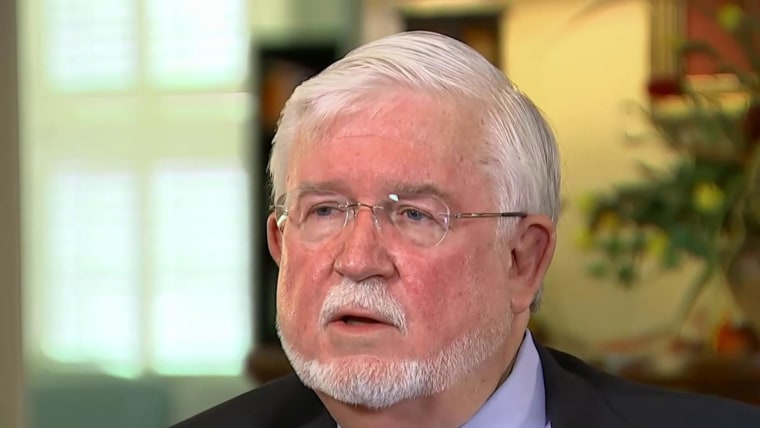

At the College of William & Mary in Virginia, Terry Meyers, chancellor professor of English emeritus and former athletic advisory committee chair, said he worked for years to persuade the school to post its athletics fee in the student catalog and in tuition bills.

“It marks a kind of dishonesty that shouldn’t be allowed at institutions of higher learning,” he said.

William & Mary’s individual student fee is now posted online. Still, Meyers believes most current students were unaware of the school’s annual $1,992 athletic fee until a student wrote about it last year in the campus paper.

Do good teams mean more applications and more donations?

Universities have defended big-time college sports as an investment that pays off in other ways, such as branding, a boost in applications and a lure for major donors.

There are anecdotal accounts of schools that have performed well in sports and have seen an increase in applications. Florida Gulf Coast University, for example, saw a 27.5 percent increase in applications after a strong run in the 2013 March Madness NCAA basketball playoffs, Bloomberg News reported in 2017.

“Successful athletics programs have identified the ‘Flutie Effect,'” said Wood Selig, athletic director of Virginia’s Old Dominion University. The phenomenon is named after Boston College quarterback Doug Flutie, whose early 1980s success boosted the school’s student applications for admission, according to a Harvard Business School study.

Selig said athletics are a part of branding at Old Dominion, which assesses students $1,678 in athletic fees per year. “Athletics can serve as a marketing tool for the university, increasing the profile of the university in the community, state, region and nation,” he said.

But Allen Sanderson, a University of Chicago sports economist, said there is little evidence that universities overall see a sustained benefit.

“One of the reasons they’re doing it is to recruit students or donors,” he said. “The evidence is fairly clear: it doesn’t help much to spend a whole lot of money on sports. There’s just not much evidence that a winning football team or an elite football team affects applicant pool or enrollment very much.”

At Eastern Washington University, school officials released a report in February analyzing the value of athletics to the school. The document notes that athletics had “no positive impact on our student enrollment, retention or recruitment.”

At James Madison, Athletic Director Jeff Bourne said, “Our senior leaders over the years have emphasized the importance of athletics in engaging support for the university among a broader audience and potentially increasing applications from other geographic regions.”

Seton Hall’s Kelchen does not doubt these benefits.

“It can do things like build school spirit. It can potentially increase alumni donations,” he said. “But it doesn’t change the fact that students are paying the bill.”

‘I don’t like it’

Students at some schools have fought the fees.

At Stephen F. Austin State University, a Division I school in Nacogdoches, Texas, students in 2016 voted down the creation of an athletics fee.

In 2019, officials at East Carolina University in Greenville, N.C., which already charged $723 a year, proposed hiking the fee by $50.

Students were upset.

“I don’t like it,” said Clay Whittington, a music student. He said the administration put in little effort to consider student concerns. “I don’t take advantage of any athletic activities and I pay full price for it.”

On Oct. 26., he tweeted a photo taken during a home football game against the University of South Florida. The stadium was two-thirds full. He tweeted at his school, “How about you stop raising our student/athletic fees if this is how empty the stadium is going to look?”

The school’s student government took the same stance. In fall of 2019, it passed a resolution against an increase in the athletics fee.

In November, however, the board of trustees approved the full increase.

To Sanderson, the economist at the University of Chicago, these are signs that there is a growing resistance to these fees.

“I think as we get more and more evidence, I think places will start scrutinizing more what they’re doing,” he said. “At some point, the students have to start asking, ‘Why am I paying $1,000 to support this football team when I have no interest in going?'”