Luciana Borio once worked on President Donald Trump’s National Security Council, but she left last year after a purge of the global health unit.

So when she realized how bad the coronavirus outbreak was likely to get — and saw that the Trump administration was not taking the necessary steps to contain it — all she could do was take her case to the public.

“Act Now to Prevent an American Epidemic,” was the headline of her Jan. 28 op-ed in The Wall Street Journal, in which she called for widespread testing and beefing up hospital preparedness. “The Wuhan coronavirus continues to spread at an alarming rate,” she warned in a subsequent op-ed a few days later.

Trump saw the situation much differently. While he blocked some Chinese nationals from entering the country in late January, his public message was simple: This is no big deal.

“We only have five people. Hopefully, everything’s going to be great,” he said on Jan. 30. A few days later, he said, “We pretty much shut it down coming in from China.”

But in fact, the Trump administration hadn’t shut down the coronavirus. The testing that Borio and other experts called for never took place, even as Trump continued to downplay the risks and make a series of false statements that experts say muddied public understanding.

As the virus continues to spread across the United States, the nation is reeling, with schools closed, sporting and cultural events shut down, and an economy in danger of lapsing into recession. As many as 50 Americans have died.

An examination of how the Trump administration responded to the coronavirus outbreak that was first documented in December reveals a story of missed opportunities, mismanagement and a president who resisted the advice of experts urging a more aggressive response. All the while, Trump made a series of upbeat claims, some of which were flatly false, including that the number of cases was declining in the U.S. and that “anybody who needs a test gets a test.”

On Friday, Trump moved to take steps that experts said should have been done weeks ago, declaring a national emergency and launching a new, broader testing program.

Trump’s own advisers acknowledged to NBC News that the failure to focus on widespread testing was their biggest misstep. The U.S. is behind most industrialized nations in understanding the extent of infection within its borders.

“If we all went back, we obviously would’ve hit on the testing part more,” one official told NBC News.

“So far, the Trump administration has failed miserably,” Susan Rice, President Obama’s national security adviser, wrote Friday in The New York Times. “The number of cases in the United States is growing exponentially, and our health system is ill equipped to determine the scope of the disease or to treat the explosion of serious cases that will almost certainly soon present.”

Missed warning signs

The outbreak began late last year, experts believe, in a seafood market in Wuhan, China.

On Dec. 31, an Associated Press report out of China was one of the first English language news accounts of a mysterious new virus.

“Chinese experts are investigating an outbreak of respiratory illness in the central city of Wuhan that some have likened to the 2002-2003 SARS epidemic,” the story began.

Initially, the language of the World Health Organization was conservative. In a statement about the disease on Jan. 14 — about the first case outside of China, in Thailand — the WHO said, “there is no clear evidence of human-to-human transmission.”

The agency soon stopped saying that, and by mid-January it was clear that the virus was spreading well beyond China.

In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warned Americans on Jan. 6 to take precautions if traveling to China. The next day, the CDC’s Emergency Operation Center activated a COVID-19 Incident Management System — an emergency management tool used to direct operations, deliver resources, and share information.

On Jan. 8, the CDC issued an alert about the disease. But the agency was without one of its crucial partners in combatting such a threat. The CDC would have worked closely with the NSC’s global health unit, but that had been disbanded.

U.S. intelligence analysts also flagged the mysterious Chinese outbreak. The National Center for Medical Intelligence, which is part of the Defense Intelligence Agency, reported in early January that 59 people had been stricken ill, a U.S. intelligence official told NBC News. Then the numbers quickly mushroomed to 548 sick and 17 dead, the official said.

“That gets your attention,” the official said.

On Jan. 21, authorities disclosed that a man in Washington state was infected, the first confirmed case in the United States.

Eight days later, on Jan. 29, Trump announced the creation of a Coronavirus Task Force to lead the U.S. response. At the time, the White House said the task force was being led by Secretary of Health and Human Services Alex Azar.

Azar was a logical choice because there was no senior person at the White House with experience in public health.

In 2018, Trump fired his homeland security adviser, Thomas Bossert, whose portfolio included global pandemics. The next month, national security adviser John Bolton disbanded the NSC’s global health unit. Rear Adm. Timothy Ziemer, the top official in charge of a pandemic response, also left his job. So did Borio, whose title was director for medical and biodefense preparedness.

None of them was replaced. That meant Trump had no top advisers in the White House with expertise in global pandemics.

“You organize your NSC around the threats you care about,” said Jeremy Konyndyk, who led the U.S. government’s response to international disasters under the Obama administration.

Pandemics were deemed a lower priority for the Trump national security team, Konyndyk and other public health experts said.

On Jan. 31, the Trump administration suspended entry into the United States by foreign nationals who had traveled to China within the prior 14 days, excluding Hong Kong and Macau. The rule didn’t apply to lawful U.S. residents and their immediate family members.

In a sense, the horse was already out of the barn. U.S. intelligence agencies had been reporting that the Chinese government was hiding the true number of infected people, current and former officials told NBC News.

“We were aware that they were not being forthright or honest with the world,” one official said.

“It’s clear that China waited several weeks to tell the world about the outbreak. Meanwhile, roughly 250,000 Chinese nationals traveled to the U.S.,” Borio and Scott Gottlieb, former Food and Drug Administration commissioner, wrote in a Wall Street Journal op-ed published on Feb. 4.

The op-ed also urged the FDA to allow private labs to develop diagnostic tests.

Let our news meet your inbox. The news and stories that matters, delivered weekday mornings.

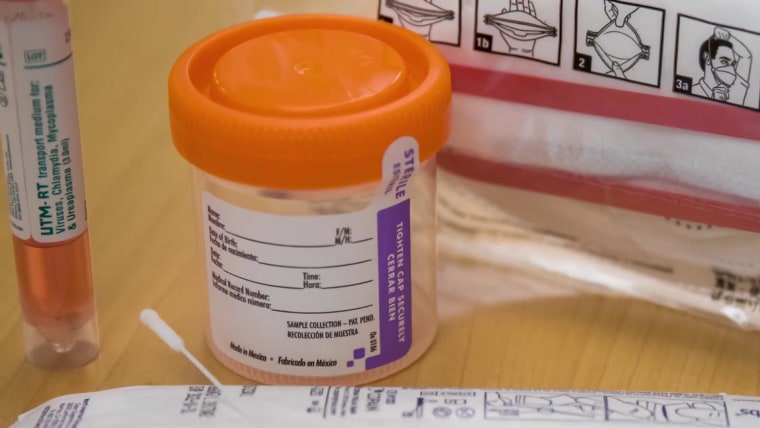

That didn’t happen, and the initial tests approved by the CDC were faulty. Moreover, the guidelines of who should be tested were narrow — only people with respiratory symptoms who had either been in close contact with an infected person or had traveled to China.

Local governments, meanwhile, took matters into their own hands. By Jan. 30, the New York City Fire Department had instructed 911 dispatchers on special procedures to follow if a caller presented coronavirus-like symptoms, including fever and cough.

In Washington, federal officials began coordinating in early January through the National Incident Communications Conference Line, an interagency response mechanism coordinated by the Department of Homeland Security.

The early discussions focused on China’s dishonesty about the number of people who contracted the virus and how to get Americans out of Wuhan province, one official said. The conversations were delicate with the Chinese government, which was threatening to retaliate economically against the U.S., and European countries, if officials leaned too heavily into the idea that a global health crisis began in China.

“They made it clear there would be repercussions,” the official said.

The U.S. banned travel to China, but the Trump administration delayed some legal actions against Chinese entities in early February that were unrelated to coronavirus out of concern that Beijing would complicate efforts to medivac Americans from China, officials said.

Among them was an indictment unsealed last week against two Chinese nationals accused of laundering more than $100 million worth of cryptocurrency that was stolen by North Korean hackers.

U.S. health officials were anxious to get CDC and outside experts on the ground in China and to get medical data from the Chinese to get a handle on the virus, but the Chinese were initially reluctant, two former U.S. officials said.

It wasn’t the first time the United States needed China’s cooperation on an international epidemic. But the crisis underlined the breakdown in relations between the two governments, former U.S. officials said. In the past, both sides maintained an established, high-level communication channel between senior figures in each capital, but that kind of pragmatic “hot line” has faded since Trump entered office, the former officials said.

Meanwhile, when the president spoke and tweeted about coronavirus in late January, he framed it as a China problem.

“We are in very close communication with China concerning the virus. Very few cases reported in USA, but strongly on watch. We have offered China and President Xi any help that is necessary. Our experts are extraordinary!” Trump tweeted Jan. 27.

Current and former officials describe a president who would get fixated on discrete aspects of the problem, from large to small, and go off on tangents about them during meetings.

Initially he was worried about worsening relations with China, they say. Then he fretted about the stock markets, and his chief goal was to stabilize a financial indicator that he’d made a central part of his re-election campaign.

Trump raged about Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell, saying his decisions had hurt the U.S.’s ability to contain the economic fallout and that he wasn’t doing nearly enough now. And at other times he zeroed in on Azar, with some people close to the president worried the HHS secretary might be fired.

At the end of February and early March, Trump had become fixated on masks. He was annoyed that the government was telling people not to wear them and would angrily ask scientists and health officials in private why — if they don’t help — do doctors wear them?

Stock market concerns

Trump stopped talking publicly about coronavirus for several weeks. On Feb. 24, amid growing public concern as the disease spread across the globe, he tweeted about the virus during a state visit to India.

“The Coronavirus is very much under control in the USA,” Trump wrote. “We are in contact with everyone and all relevant countries. CDC & World Health have been working hard and very smart. Stock Market starting to look very good to me!”

The next day, a senior health professional gave the opposite message.

“It’s not so much of a question of if this will happen anymore but rather more of a question of exactly when this will happen,” Dr. Nancy Messonnier, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, told reporters in a news briefing.

She spoke of the need to mitigate the damage rather than contain the spread. She said she told her own children that “as a family, we need to be preparing for significant disruption in our lives.”

“We are asking the American public to work with us to prepare, in the expectation that this could be bad,” Messonnier said.

Nobody at the White House had been saying anything close to that in public. Stock prices plummeted after the news conference.

Trump was furious, people briefed on the matter told NBC News, and urged that Messonier be muzzled. She has continued to brief reporters but her tone appeared to change.

The president was on his way back from India, where he’d continued to provide a rosy outlook on the virus. He believed the risk to Americans was low, and that comments like Messonier’s would spook the financial markets.

Messonnier‘s remarks forced the White House to play catch up at a time when public criticism of Trump’s handling of the crisis was ramping up. Until then, the White House had treated the outbreak as a foreign threat. Now, the administration was struggling to pivot to the problem of mitigation, and get control of a narrative that had spun out of its control.

Officials scrambled to craft new talking points and fact sheets, according to people familiar with the matter, and Trump repeated some of them publicly.

But the president could not bring himself to sound the alarm. He continued to suggest that the news media was blowing the outbreak out of proportion. He was aided by allies in the right-wing media, who trumpeted the same message.

“Low Ratings Fake News MSDNC (Comcast) & @CNN are doing everything possible to make the Caronavirus look as bad as possible, including panicking markets, if possible,” Trump tweeted Feb. 26. “Likewise their incompetent Do Nothing Democrat comrades are all talk, no action. USA in great shape! @CDCgov”

The lack of testing continued to pose a problem. The U.S. was testing fewer people per capita than any developed country.

The reason was that under federal rules, only the CDC, a small government agency, could conduct approved tests.

Private labs were in discussions with CDC in late February about developing their own tests, but the CDC inexplicably told them that was unnecessary because there wasn’t a great demand, a source familiar with the matter told NBC News.

It wasn’t until Feb. 29 that the FDA announced more lenient guidelines that sped up the authorization process for commercial, academic, and hospital labs to conduct their own tests.

“Nobody at a higher level was saying wait a second, this is completely unacceptable. We need to act with extreme urgency and get this out to the states on an expedited basis,” said J. Stephen Morrison, senior vice president at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, which released a report last year on the U.S.’s vulnerability to global health security threats.

Critical time was lost. “Time is the most important element. The loss of time is the most dangerous thing in an epidemic,” Morrison said.

The administration’s approach initially was based on a narrow view of the virus that turned out to be deeply flawed. Testing was focused on people who traveled to or had been in contact with cases linked to China, and failed to take into account the risk that other Americans — with no links to China — had been infected.

“That basically meant they were only looking for one type of transmission,” Konyndyk said. “It was built on a logical fallacy.”

Throughout January and February, the administration had “a cautious, plodding approach,” said Morrison. “They were fumbling around and it wasn’t clear who was in charge.”

There was no clear chain of command, and no single figure with access to the president to move the machinery of government.

By the end of February, Trump named Vice President Mike Pence to lead a task force on the outbreak, effectively recreating a White House global health team that had been dismantled in 2018.

Critics of the administration also say the White House should have moved earlier and more decisively to secure emergency funding for public health agencies to handle the epidemic weeks earlier. Lawmakers pushed for the funding, and for a higher figure than initially proposed by the White House.

On March 6, Trump traveled to CDC headquarters in Atlanta and made a series of comments many observers found startling, even for this unorthodox president. Some of them were inaccurate.

Trump said he “wouldn’t generally be inclined” to cancel travel and social gatherings.

He said he would have preferred not to allow 3,533 people on board a cruise ship held off the coast of California to enter the United States, because it would boost the number of infected Americans.

“I would like to have the people stay,” he said. “I told them to make the final decision. I would rather — because I like the numbers being where they are. I don’t need to have the numbers double because of one ship that wasn’t our fault.”

On testing, Trump said something that many considered a lie, because they believed Trump had to have known it wasn’t true.

“Right now and yesterday, anybody that needs a test gets a test,” he said. “They’re there, they have the tests, and the tests are beautiful. Anybody that needs a test gets a test.”

The Trump White House continued to balk at health professionals who wanted to issue stark advice, officials told NBC News. One example: The CDC wanted to recommend that anyone over 60 remain inside their homes whenever possible, but was told not to say that by Trump administration officials, three people familiar with the matter told NBC News.

Instead, on March 9, Messonier stressed that people in that cohort faced higher risks of infection and complications and should consider that as they plan their daily lives.

That same day, Bossert, Trump’s former pandemic adviser, published an op-ed in the Washington Post expressing what he had been saying for days on Twitter: The U.S. needed to take dramatic action to stop a looming public health crisis, including “school closures, isolation of the sick, home quarantines of those who have come into contact with the sick, social distancing, telework and large-gathering cancellations.”

In Italy, where the spread of the virus was ahead of the U.S., overwhelmed doctors were reporting of war-like conditions in overtaxed intensive care units, and of having to ration care and equipment. The U.S. would experience that same nightmare scenario if nothing changed, Bossert said.

“We’re 10 days away from our hospitals getting creamed,” he told NBC News.

Trump administration officials were annoyed, but they knew they had to do something. They scheduled an Oval Office address in prime time Wednesday, only the second time Trump has done that in his presidency.

Reading from a teleprompter in an unusually subdued tone, Trump announced a ban on travelers from Europe and a series of economic measures, but said nothing about testing, about strategies to stop the spread, or about what his experts were telling him about possible public health scenarios.

The speech was widely panned, and stock markets tanked the next day.

In the absence of federal leadership, local governments and private organizations began to make dramatic decisions on their own. The NBA and NHL suspended their seasons. States began to order school closures. Corporations ordered halts to business travel and urged employees to work from home.

“The U.S. government’s slow and inadequate response to the new coronavirus underscores the need for organized, accountable leadership to prepare for and respond to pandemic threats,” Beth Cameron, who served as the senior director for global health security and biodefense on the White House National Security Council under Obama and in the early months of the Trump administration, wrote in a Washington Post op-ed published Thursday.

On Friday, Trump declared a national emergency and announced a new drive-through testing regimen. The stock market soared, gaining nearly 2,000 points. But health officials said there are many difficult weeks to come.

Asked by NBC’s Kristen Welker whether he took responsibility for the delay in widespread testing, Trump answered, “I don’t take responsibility at all.”