The good news is that America’s national security institutions have a massive capacity to help the country fight its latest war, the one on the deadly and highly contagious COVID-19. The bad news is that their commander-in-chief, President Donald Trump, failed to mobilize them in advance to fully harness their power — and continues to be reluctant to do so even now.

While doctors and civilian hospitals must staff the front lines of this war, national security instruments such as military units and medical stockpiles, combined with laws designed for wartime use, can play an important role in supporting them.

The initial and ongoing failure to fully employ these means in the face of a crisis with the potential to kill as many Americans as a world war is nothing short of unconscionable.

But getting them in usable shape takes time, especially because the military is a sprawling and bureaucratic beast. To do so in a way that could have helped blunt the worst of the crisis would have meant acting as soon as the threat appeared in January.

The initial and ongoing failure to fully employ these means in the face of a crisis with the potential to kill as many Americans as a world war is nothing short of unconscionable.

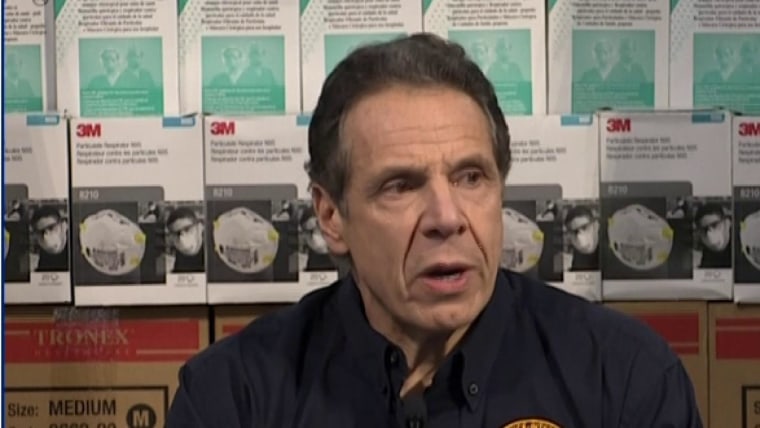

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo called out the federal government directly for the fiasco Tuesday, declaring at a news conference that it was “inexplicable” that the massive capabilities of the U.S. military were being stalled while hospitals in his state, the hardest hit by the virus so far, lacked colossal amounts of lifesaving supplies and equipment.

He particularly slammed the White House’s dithering on invoking the Defense Production Act to provide the capital needed for businesses around the country to expeditiously ramp up production. “I do not for the life of me understand the reluctance” to use the act, he told reporters.

Get the think newsletter.

While the federal government’s refusal to do everything it can to combat the illness at this moment is egregious and troubling, the problem is more deep-seated than the present inaction. It starts with the basic prioritization of this issue as demonstrated in our national budget. In 2019, the United States allocated $738 billion in defense spending, with an emphasis on developing capabilities to fight great power conflicts with the likes of China and Russia. The same year, it spent less than one-100th of that amount — $6.5 billion — on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Of that pool of money, less than 10 percent went to combating “emerging and zoonotic infectious diseases,” of which the coronavirus fits the bill. Over a month after the initial coronavirus outbreak in China, the Trump administration proposed reducing CDC funding by almost 16 percent.

There’s also a misguided mindset. In 2014, nearly 3,000 U.S. military personnel were deployed to Africa and helped contain and kill an Ebola epidemic before it could spread around the world. But due to the nationalistic mentality of the Trump administration, the U.S. did little to aid in the fight abroad against the coronavirus. Now it’s far too late to fight the disease overseas, so the battle must take place on American soil.

Fortunately, the military has extraordinary logistics and command-and-control capabilities that can be used to coordinate distribution of lifesaving medical supplies across the country. The 32,000 personnel of the Army Corps of Engineers can rapidly build the facilities to absorb the huge influx of patients COVID-19 is already producing. And it has tens of thousands of medical personnel who could take on routine cases so civilian doctors can focus on fighting the virus.

Yet until a week ago, most of these tools of state power were left untapped and immobilized — an oversight that could cost thousands of lives. There was no leadership at the apex of the U.S. government that compelled those institutions to act, even though The Washington Post recently reported that U.S. intelligence services had been steadily reporting that a global pandemic was likely since January.

Deploying these resources takes time to organize and requires that money be appropriated. In fact, in March, the Army reported it was still short by $1 billion in funding it needed to prepare for the pandemic. In addition, reserve personnel must be called up for duty, but the process is complicated because the Pentagon wants to ensure it doesn’t call up personnel already fighting COVID-19 as civilian doctors.

The U.S. could have at least spent the last two crucial months following the outbreak in Wuhan, China, launching an emergency expansion of the U.S.’s Strategic National Stockpile of emergency medical supplies, which receives only $600 million in funding a year — little more than the cost of a single small warship. The stockpile has only 42 million medical masks at its disposal, barely more than 1 percent of the 3.5 billion estimated to be necessary to deal with the pandemic.

But not only did the president and senior officials fail to do these things, they also publicly downplayed COVID-19’s dangers. Furthermore, leaders in the Pentagon itself have been reluctant to engage in the coronavirus fight, preferring to focus on the threat of international conflicts.

Even when steps have been taken, they’ve been handicapped by the late start and other deficiencies. For example, New Yorkers welcomed the news that the Navy hospital ship USNS Comfort would deploy to New York City, the metropolis hardest hit by the disease, with over 14,904 cases confirmed as of Tuesday. The huge ship has facilities for 1,000 patients, including 80 intensive care units that can be used to treat trauma cases so civilian hospitals can fully dedicate themselves to treating diseases.

Unfortunately, the Comfort had been undergoing maintenance, so it will not be ready to deploy for weeks — a delay that might have been avoided if preparations had begun earlier. Likewise, it’s regrettable that the praise-worthy initiatives to use the Army Corps of Engineers to hastily convert abandoned buildings into hospitals didn’t begin sooner so the facilities could begin receiving the huge spike of patients expected in March and April. But they hadn’t received orders to do so until last week.

Of course, using these military resources isn’t a panacea for other reasons. It bears recalling that when the Comfort deployed in response to a hurricane that ravaged Puerto Rico, it arrived well after its resources were most needed and admitted only six inpatients a day because of mismanagement and excessive red tape. A journalist observed “dozens of people waiting to see doctors in the tents set up outside, but inside most of the beds were empty.”

Perhaps most outrageous, however, has been the vacillating over invoking the Defense Production Act, a law that allows the president to compel companies to produce items deemed necessary for national security and grants federal authority to manage the distribution of strategic resources.

On Friday, Trump claimed he was invoking the act — but he later stated that he would refrain from using the powers broadly, arguing: “The federal government’s not supposed to be out there buying vast amounts of items and then shipping. You know, we’re not shipping clerks.”

His comments came as hospitals in the wealthiest nation on the planet were already running out of masks and ventilators well before the virus reaches its peak — a problem that’s only metastasizing. The CDC is telling doctors and nurses to use expired masks or improvise by re-using single-use N95 masks.

China, by contrast, has shown no squeamishness about commanding companies to produce masks, even if that means iPhone manufacturers are switching to making cheap but lifesaving medical equipment. As a result, it has multiplied production 20 times over to 200 million masks a day (which it is keeping in country).

Deploying these resources takes time to organize and requires that money be appropriated. In fact, in March, the Army reported it was still short by $1 billion in funding it needed.

Trump officials are resisting adopting such policies, which contravene their belief in free-market capitalism. Instead, Congress has passed a bill to protect mask manufacturers from legal liabilities, which is hoped to increase mask production by tens of millions annually — to around one-seventh of the estimated 3.5 billion masks that will likely be needed to deal with the pandemic. Just as scary is a massive shortage of thousands of ventilators. When there aren’t enough ventilators, doctors must decide to allow some treatable patients to die so that others can live.

If the United States really does commit itself to a protracted fight against the coronavirus — no, not some “15 days” solution born of magical thinking — it can surely mobilize the national security infrastructure’s immense industrial, medical and logistical resources to save the lives of hundreds of thousands of people and contain the pandemic. But that will require national leaders to stop dragging their feet and adopting half measures. They must realize that they are locked in a war to save Americans from an implacable enemy and that every possible resource is needed.