WASHINGTON — It was a message that was perfectly timed, seeking to reassure a young Iranian monarch in crisis. And it came from the world’s most prominent royal, Britain’s Queen Elizabeth.

But it soon became clear there was no such message from London. It was a snafu, a garbled diplomatic note and a case of mistaken identity the Americans continued exploiting for their own purposes even after realizing their mistake.

According to “The Queen and the Coup,” a documentary airing this month in Britain citing newly discovered U.S. documents, the comedy of errors may have played a key role in the 1953 CIA-British coup that toppled the democratic government of Iran.

The 1953 takeover, which restored Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi of Iran to power and has fueled distrust between the U.S. and Iran ever since, has inspired numerous books, documentaries and academic research. But nearly seven decades later, British historians have uncovered State Department documents in U.S. national archives that reveal a new twist in the run-up to the coup.

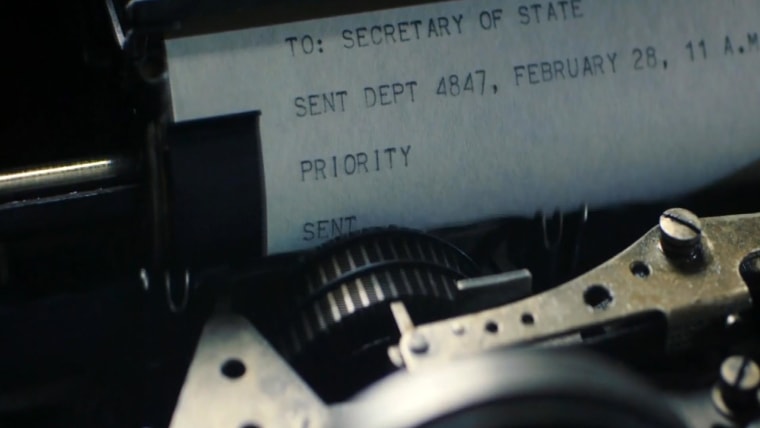

The key document comes from February 1953, five months before British and U.S. spies helped overthrow the parliamentary government led by Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh. The shah of Iran was teetering, and considering fleeing the country, which would effectively wreck the joint British-U.S. plot before it even began.

The document had never come to public attention until now, even though it had been declassified along with other documents in the U.S. archives, according to the documentary produced by Brave New Media for Britain’s Channel 4.

On Feb. 27, the U.S. Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles, received a “top secret’ cable from the American embassy in London relaying a message from Britain’s Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden, saying:

“Foreign Office this afternoon informed us of receipt message from Eden from Queen Elizabeth expressing concern at latest developments re Shah and strong hope we can find some means of dissuading him from leaving the country.”

The extraordinary message appears to read as if Queen Elizabeth is appealing to a fellow monarch to remain resolute.

Washington viewed the message from Britain as an ace card to convince the shah to stay put, said Rory Cormac, professor of international relations at the University of Nottingham, one of two scholars who unearthed the documents.

For the Americans, “this is great,” Cormac told NBC News. “This is ammunition that we can use from somebody whom the shah really respects, the queen, the leader of the global royal families.”

The U.S. ambassador in Tehran, Loy Henderson, promptly requested a meeting with the shah to deliver the message from Britain, according to the documentary, citing Henderson’s account sent back to Washington. A palace aide told the ambassador the shah could not meet in person because he was expecting Prime Minister Mossadegh to arrive to “bid him farewell.”

Let our news meet your inbox. The news and stories that matters, delivered weekday mornings.

Henderson expressed concern as to whether the phone was secure and then tried to convey his message to the shah via the palace official, using discreet language.

Although there is no way to know what the shah made of the message, he quickly dropped his plans to fly out of Tehran, said Richard Aldrich, professor of politics and international studies at the University of Warwick, the other scholar who discovered the papers.

“He does a U-turn,” Aldrich said.

“What we would really like to do as historians is to be able to set up a laboratory and rerun the events and change that one thing, but you can’t do that. But my assessment is, that this coup would have been much, much less likely to have happened if the shah had fled,” he said.

In London, however, the U.S. embassy soon realized the message it had passed on from British officials could easily be misunderstood.

Citing its earlier telegram, the embassy says the reference to “Queen Elizabeth refers of course to vessel and not – repeat not – to monarch,” according to a second note recounted in the documentary.

The British Foreign Secretary had sent his message on board a ship, the RMS Queen Elizabeth, as he headed to Canada for meetings. There was no message for the shah from the queen. There was no top-secret royal diplomacy in play. It was just a blunder caused by a confusingly written note.

“It’s poorly drafted, and I wouldn’t blame the Americans at all for misreading it,” Cormac said.

In its telegram to Washington, the London embassy wrote: “deeply regret lack of clarity. It was not, repeat not, until re-reading the message this morning that it occurred to us that it was open to misinterpretation.”

U.S. officials decided not to tell their British counterparts about the mix-up. The British government would have been outraged to hear the queen was being invoked as a tool in a covert regime change operation, Cormac said.

And as for the shah, the Americans chose not to correct the record.

“They don’t want the shah to realize that essentially he’s been misinformed, perhaps even unintentionally duped,” Aldrich said.

“He’s been persuaded to take risks . . . And all this to some extent is on a false premise. He believes he has received a message from one monarch to another. He’s actually received a message from a boat.

“Not quite the same thing.”

The coup to topple Mossadegh was launched in August of the same year. After Mossadegh’s government had shut down the British embassy in Tehran in 1952, suspecting it was a center of espionage, the CIA took the lead in running the coup operation using British agents and plans. President Harry S. Truman’s administration had resisted the idea of ousting Mossadegh. But after Dwight Eisenhower’s inauguration in January 1953, a more hawkish team — worried about the Soviet Union gaining a foothold in Iran — backed the British approach.

Relying primarily on Iranian military officers, bribery and exploiting existing opposition to Mossadegh, the coup — dubbed “Operation Ajax” by the CIA — initially faltered, with Mossadegh’s camp getting wind of the plot.

But CIA officers on the ground, led by Kermit Roosevelt Jr., the grandson of former President Teddy Roosevelt, staged a second attempt that succeeded.

On Aug. 19, the shah dismissed Mossadegh as prime minister and installed a military government. In 2013, the CIA publicly admitted for the first time its involvement in the 1953 coup, an event that continues to shape the troubled relationship between Iran and the United States.

The shah himself was overthrown in the 1979 Iranian revolution following mass protests. Students and other opposition activists cited the 1953 coup as a partial justification for the revolution.

The revelation about the 1953 diplomatic notes raises the question of whether the British queen ever knew she had an inadvertent role in the events in Iran, or whether British officials ever sought to invoke the British royal in other geopolitical machinations, Aldrich and Cormac said.

But gaining access to historic documents related to the royal family is extremely difficult and often impossible, even for papers from the 19th and 20th centuries, the historians said.

“The most secret institution in the United Kingdom, by a long shot, is the royal family,” Cormac said.

After the takeover in 1953, the American ambassador in Tehran proposed to London some sort of congratulatory message to the shah from British Prime Minister Winston Churchill or from the queen, according to the documentary.

The British Foreign Office shot back: “I do not think there can be any question of the Queen sending a message!”