At a briefing this week, New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy touted his state’s efforts to trace the spread of the coronavirus, outlining plans to hire 1,600 contact tracers who will call people who may have been exposed to the coronavirus.

Not part of his plan: a smartphone app to help with contact tracing.

“The state of New Jersey is neither pursuing nor promoting exposure notification or digital alerting technology, at least at this time,” Murphy said.

New Jersey isn’t alone. States that had committed to using contact tracing apps or expressed interest are now backing away from those claims. The few states that have rolled them out have seen only tepid responses. And there are no indications of any momentum for the apps at a national level.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom was an early supporter of contact tracing apps, saying on the same day that Google and Apple announced a joint project that he wanted to “build that capacity and partnership” as part of the state’s plans. Two months later, the nation’s most populous state isn’t using any apps or cellphone tracking technology, said Ali Bay, a spokesperson for California’s Public Health Department.

“Most of the contact tracing work (notifying people who have been in close contact with an infected person to prevent the disease from spreading to others) can be done by phone, text, email and chat,” Bay said in an email. She declined to elaborate on the shift in plans.

Most states are giving the cold shoulder to smartphone apps. A survey of state health officials from Business Insider this week showed that only three states — Alabama, North Dakota and South Carolina — said they were going to use the software provided by Apple and Google. The number hasn’t grown since the same three states reported interest last month, and none has launched an app with the Google-Apple software.

“The factual analytical assessment is it’s not a high upside,” said Andy Slavitt, an Obama administration health care official who is chair of the nonprofit United States of Care. “The bulk of the investment you need to make is in manpower.”

It’s not the enthusiastic welcome that some technologists were hoping for when they began planning months ago for the launch of smartphone apps that would help respond to the pandemic and contribute to a return to something like normal life.

Even the World Health Organization has piled on.

“Digital tools do not replace the human capacity needed to do contact tracing,” WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said at a briefing this week, adding that more evidence was needed and that the WHO would convene experts to share information.

And while there are early reports of successful mobile tracing technology in some countries, such as South Korea and Taiwan, the efforts so far have fallen flat in the U.S.

“It is something that launched and then sort of fell away,” said Ryan Calo, a University of Washington law professor and expert in tech policy and privacy who was an early skeptic that the apps could be effective. He said it makes sense for states to focus on human contact tracers, who “have been effective since the bubonic plague.”

The proposed apps were the result of a frenzy of activity among technologists searching for a way to help stem the pandemic in its earliest days.

Beginning in February and into March and April, groups of academic researchers and corporate software engineers popped up worldwide to figure out the technology behind digital contact tracing — something that had never really been attempted before. They used Slack, Google Docs and other collaboration tools to wrestle with complicated issues, such as whether an app would use Bluetooth technology or GPS tracking.

Then, after the urging of dozens of outside experts, Google and Apple agreed to add their heft to the idea with a rare joint effort, giving the decentralized efforts the feel of a real and unified movement that had momentum.

Representatives for Apple and Google didn’t respond to requests for comment or for information about how many public health authorities are using their code, known as an application programming interface, or API.

A handful of states — North Dakota, South Dakota and Utah — launched apps without the support of Apple and Google, but none saw widespread adoption. More states, including Washington, have considered doing so or have launched test versions, and it’s possible that apps will gain momentum closer to the fall, when they might be taken up by more employers, schools and universities and at related football games.

“I do think employers and sports leagues, when they get going, may require people to keep these kinds of logs to account for what’s happened since people were tested. I think there will be some targeted use,” Slavitt said.

In a partnership between the University of Washington and Microsoft, more than 30 people are working on a contact tracing app, but they are aiming only for a limited release at the university in the fall after testing this summer, said Nola Klemfuss, a spokesperson for the project at the university.

A separate group, Covid Watch, is planning a test at the University of Arizona. “If we show it works, I think that will help,” said Tina White, the executive director. “Governors are thinking about it, even though they’re being skittish.”

In South Carolina, an app is still under development and hasn’t been approved or reviewed by state authorities, said Heather Woolwine, a spokesperson for the Medical University of South Carolina, which is building the app. “Unfortunately, Apple and Google released information about our app prematurely and without official approval,” she wrote in an email. (The companies didn’t respond to a request for comment on the release.)

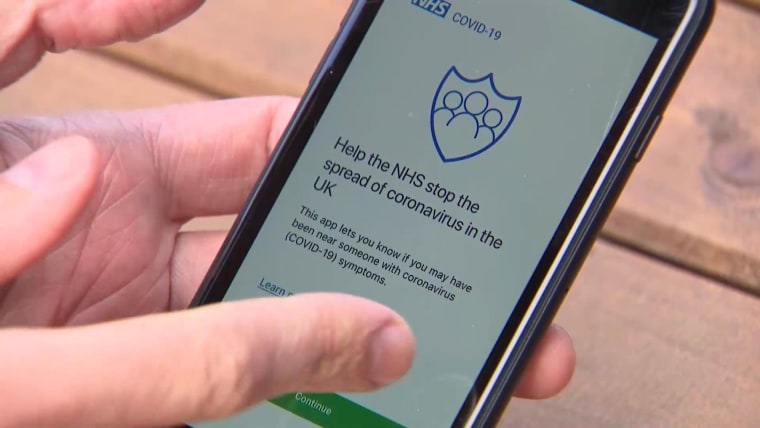

The experience with contact tracing apps has also been mixed abroad. Britain’s National Health Service has been testing an app. In Singapore, home to an early tracing app, adoption is uneven, and the government has considered rolling out a separate, wearable device for tracking. Interest in Australia fell as people’s perception of coronavirus risk declined. Germany is expected to launch its app within days.

The general idea behind many of the apps is to use Bluetooth signals to determine whether two phones have been in close proximity, such as within 6 feet, and to send a notification if a person was near someone for several minutes who later tested positive for the virus.

At some point, some of the developers behind the efforts renamed the apps as “exposure notification” projects rather than contact tracing — in effect, removing a connotation about tracking while also possibly lowering expectations of what the apps were going to do.

It’s not always clear what has scared off U.S. governors, whose support is essential if any apps are going to succeed. In New Jersey, for example, an aide to Murphy didn’t respond to a request for more information about the governor’s position.

Another possible factor that is out of technologists’ and governors’ control: the absence of a cohesive national plan for contact tracing, the lack of which has hobbled states as they’ve searched for money and resources to launch their own programs. Neither the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention nor the White House has endorsed the app technology.

“The CDC and Google and Apple should have gotten together and built an app. Instead, we have a state-by-state response,” said Tarun Nimmagadda, founder of Corona Trace, one of the early nonprofit efforts to build an app. He said he’s given up trying to get the attention of governors and is instead looking at for-profit software to sell to employers.

But there were obstacles to the technology from the beginning, including ones that were well known even to supporters of the apps. It might require adoption by a majority in a given area to have the most impact, and it was unclear whether the Bluetooth technology used many of by the apps could provide the level of precision necessary to calculate people’s risk of exposure.

And there was the privacy obstacle: building apps that would collect as little personal information as possible and keep any data that was collected secure, all while reassuring potential users that they were safe.

Early apps haven’t always passed the test, sometimes sending data to other apps or including unneeded lines of computer code associated with advertising.

The slower timeline of launches isn’t necessarily a bad thing, because it gives software developers more time to get the technology right, said Andreas Gebhard, a co-founder of the TCN Coalition, a group of technologists supporting app development.

“With something that is supposed to notify people about potential health concerns, you have to do a lot more legwork before you release it,” Gebhard said, adding that the stakes were higher than for, say, a simple note-taking app.

“I think everyone still feels that this has a lot of potential,” he said.

Calo of the University of Washington said the tech industry has helped fight the pandemic in numerous other ways, from providing charitable contributions to an unprecedented effort to take down social media posts with bad health advice or medical misinformation.

And even if contact tracing apps don’t eventually succeed, Silicon Valley has made it clear that it tried.

“If Trump comes along and says, ‘What have you done?’ they can say, ‘Well, we provided this API, and we can’t help it if the states aren’t using it.’ So they’ve sort of discharged their obligation,” Calo said.