President Donald Trump’s re-election campaign is fighting a group of Navajo Nation citizens who want Arizona’s mail-in voting requirements changed in line with a dozen other states, for fear that ballots sent from the tribe’s reservation won’t be counted in the November election.

The motion filed Thursday in federal court by the Trump campaign and other state and national Republican committees attempts to undercut the message of six Navajo plaintiffs who say in a lawsuit that the state’s current stipulation — that mail-in ballots must be received before 7 p.m. Nov. 3 instead of postmarked by that date — could disenfranchise Native American voters.

“Plaintiffs seek to create a race- and geography-based exception to a long-standing, generally applicable state law that would give certain citizens more time to return their requested early ballots than every other Arizona voter in the upcoming General Election,” Brett Johnson, an attorney for the campaign, wrote in the filing.

“What is more, Plaintiffs’ unwarranted delay in bringing their claims on the eve of a General Election threatens the orderly administration of that election,” the motion continued, adding that changing the deadline rule “would unquestionably affect the share of votes that candidates in the State of Arizona receive.”

The filing, however, does not specify which political party would gain from the counting of late-received ballots. Neither Johnson nor the Trump campaign immediately returned requests for comment Friday.

Arizona’s 7th Legislative District, which includes a large portion of the Navajo Nation, is majority Native American, and the Democrats have a 2-to-1 advantage of registered voters over the Republicans, state election data shows.

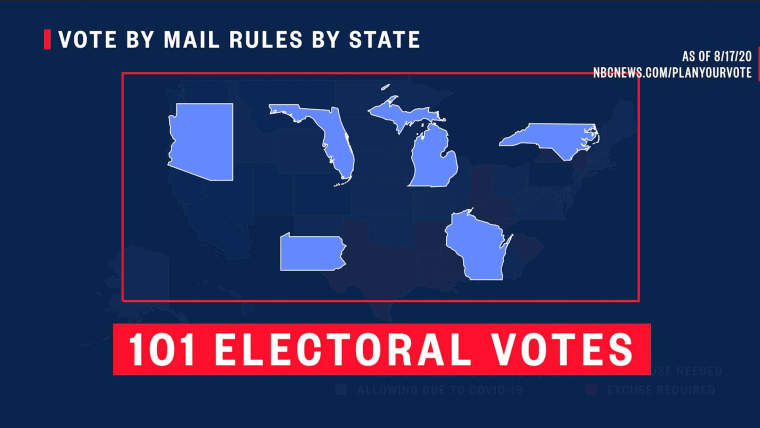

While most states don’t allow mail-in ballots to be counted if they’re not received on Election Day, more than a dozen do, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures, including battleground states such as Nevada, North Carolina, Ohio and Virginia.

The Navajo Nation plaintiffs are suing Arizona Secretary of State Katie Hobbs, a Democrat who oversees elections in the state and certifies results. They allege the state’s requirement for mail-in ballots places “unconstitutional burdens” on them, particularly amid a backdrop of the coronavirus pandemic and concerns in recent weeks over threatened operational changes with the U.S. Postal Service.

The plaintiffs in their Aug. 26 lawsuit are asking for Arizona to count all ballots sent by members of the Navajo Nation postmarked on or before Election Day and received within 10 days.

To support their claim that mail service to and from the reservation, which is largely rural, is slower than off tribal lands, the suit provides several examples of the discrepancies for how long it took to mail a first-class envelope through the Postal Service.

In some cases, it took between six to 10 days to arrive at the nearest county recorder’s office after traveling about 100 to 200 miles in the experiments, according to the suit. By comparison, the suit said, mail sent from the affluent Phoenix suburb of Scottsdale arrived at the local county recorder’s office in less than 18 hours.

But the Trump campaign’s filing argues that requiring election offices to count ballots differently depending on where they came from would only “sow confusion and delay in the administration of the upcoming General Election and all future elections.”

Oct. 23 is the last day for Arizona voters to request a mail-in ballot, which means they have about 10 days to ensure it is returned in time for Election Day.

OJ Semans Sr., co-executive director of Four Directions, a Native American voting rights group assisting in the plaintiffs’ lawsuit, said many Native Americans would prefer to vote in-person, but the pandemic has thrown many voters on reservations for a loop this year, particularly in the hard-hit Navajo Nation.

Navajo Nation citizens face a multitude of hardships when it comes to voting by mail, Semans added, including that many on the reservation don’t have traditional addresses and mailboxes, going to the nearest post office is difficult because there’s only one for every 707 square miles on the reservation, and less than one-third of tribal households own a car.

Affording extra days to count ballots from tribal residents is “really just a common sense request,” Semans said, adding that Hobbs could choose to expand that decision to all Arizona residents if people are concerned it gives Navajo voters an “advantage.”

However, Hobbs said in a statement that the deadline remains set by state law, and that for now, her office will do what it can to ensure all people voting by mail have enough time to send out their ballots.

While “I understand their concerns … under the current circumstances, we have to make sure voters are aware of the options available to them,” she said. “This includes returning a ballot-by-mail as soon as possible or taking it to a secure drop box or a voting location.”

A spokeswoman for Hobbs said that if the court rules differently, she will comply.