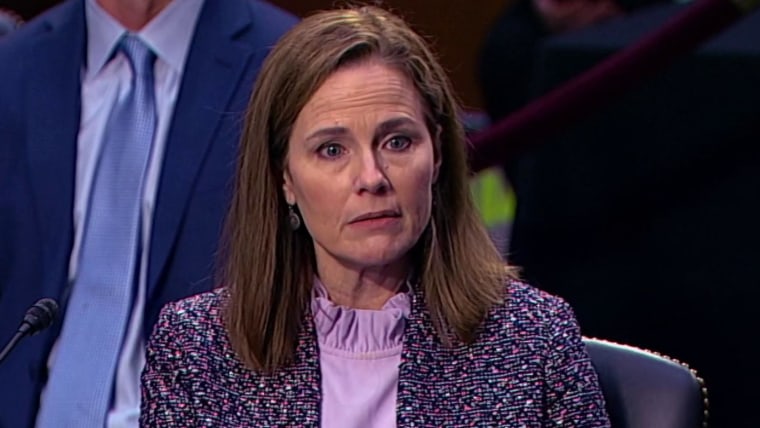

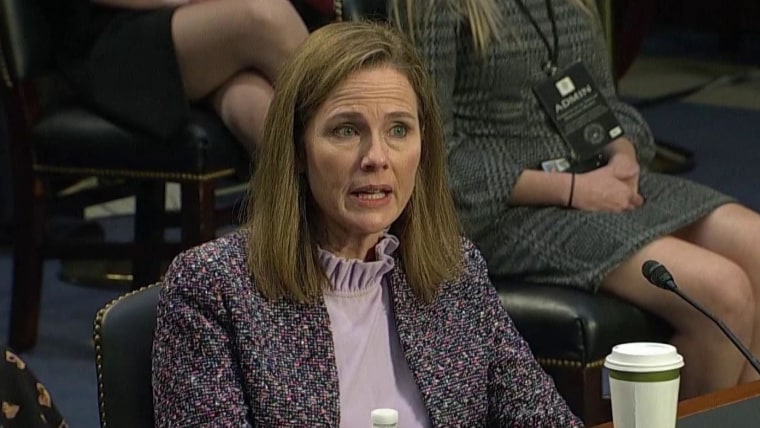

WASHINGTON — Many of Amy Coney Barrett’s dodges before the Senate this week have followed in the tradition of Supreme Court nominees declining to prejudge issues that could come before them. But some raised eyebrows from legal scholars as being unusual.

Some of the evasions appeared carefully crafted to avoid contradicting President Donald Trump, the man who nominated her for the court, even as they required her to refuse to answer straightforward or noncontroversial legal questions.

“She’s gone further than other candidates in refusing to answer questions. Her view is that she’s got the votes and it doesn’t matter — that she’s not going to get denied confirmation for failure to answer,” Erwin Chemerinsky, a law professor at Berkeley Law, said.

Barrett wouldn’t say if a president has unilateral authority to delay an election, saying it’d make her a “legal pundit” to speculate. Legal scholars point to language in the Constitution that explicitly gives that power to Congress.

She wouldn’t say if the president should commit to a peaceful transfer of power if he loses an election conducted in accordance with the law, saying that was “pulling me in a little bit into this question of whether the president has said that he would not peacefully leave office.”

“And so, to the extent that this is a political controversy right now, as a judge, I want to stay out of it, and I do not want to express a view,” Barrett told Sen. Cory Booker, D-N.J.

She declined Wednesday to say whether mail-in or absentee ballots were an essential way for Americans to vote in a pandemic. “That’s a matter of policy on which I can’t express a view,” she told Sen. Amy Klobuchar, D-Minn., who chafed at her response.

The common thread behind those nonresponses: Trump’s Twitter account.

He has floated delaying the election, which he lacks the power to do. He has refused to commit to stepping down and peacefully transferring power if he loses the election. And he has made unsubstantiated claims linking mail-in ballots to voter fraud.

The hearing felt perfunctory at times with even Democrats occasionally conceding that the conservative jurist is likely to be confirmed. The 48-year-old Barrett needs 50 Senate votes to secure a lifetime appointment to the Supreme Court.

There are 53 Republicans in the chamber, and just two have indicated opposition to confirming a nominee this close to a presidential election.

With little risk of losing another Republican vote, Barrett lacked an incentive to contradict Trump’s legally dubious assertions or weigh in on political controversy.

Chemerinsky said it is “absolutely clear” that a president has “no authority under the Constitution to delay the election.” He said there’s “never been an issue in all of American history” with the legal mandate for a president to step down after losing an election.

For Barrett to point out the invalidity of those claims, particularly in response to questioning from Democrats hostile to Trump, carried possible brushback from a president who demands personal loyalty and can lash out unpredictably when he doesn’t receive it.

Jonathan Adler, a law professor at the Case Western Reserve University School of Law, said the senators asking those questions were trying to put Barrett in an uncomfortable predicament, rather than learn about her judicial philosophy.

“These are all matters of contemporary political discussion given the president’s various comments and the (justified) criticism that has been made of such comments,” Adler said in an email. “All such questions are efforts to put the nominee in a compromised position by forcing them to choose between criticizing the President or refusing to affirm an obvious principle.”

Barrett frustrated Sen. Dick Durbin, D-Ill., on Wednesday by refusing to say whether a president could unilaterally deny an American the right to vote on the basis of a person’s race, telling him, “I really can’t say anything more than I’m not going to answer hypotheticals.”

Those dodges had nothing to do with the Ruth Bader Ginsburg standard of not hinting at how she would rule on litigation that could come before her, which Barrett invoked repeatedly to avoid discussing her legal views on the Affordable Care Act or abortion rights. She also refrained from weighing in on policy matters pertaining to Trump’s family separation measures or climate change.

To the extent that Barrett separated herself from Trump, it was to insist that she would be judicially independent and not blindly follow the president’s preferences to overturn the Affordable Care Act and overrule Roe v. Wade, which he has said he expects of his judge picks.

Barrett wouldn’t say Wednesday if a president could pardon himself, which Trump has asserted the right to do. She said such a question “calls for a legal analysis of what the scope of the pardon power is.”

But she did say later in the day, broadly, that “no one is above the law in the United States.”