Hany Farid is well versed in how Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., speaks.

“So, Sen. Warren has a habit of moving her head left and right quite a bit,” said Farid, a computer scientist at the University of California, Berkeley.

Farid’s expertise comes from his hours working with authentic videos of Warren and other politicians in hope that technology can prevent the spread of fake videos — the computer-generated “deepfakes” that are seen as the new frontier in online misinformation.

Former President Barack Obama has his own quirks.

“President Obama had this thing that when he delivered bad news, he would frown and he would tilt his head downward a little bit. Very characteristic,” Farid said. “They all have their own little tells.”

Farid is part of a team of researchers at the University of California, Berkeley who have developed a computer algorithm that they say may help to detect deepfakes. It’s meant to work quickly out of fear that a viral deepfake will need almost immediate identification and response.

“What we are concerned about is a video of a candidate, 24-to-48 hours before election night,” Farid said. “It gets viral in a matter of minutes, and you have a disruption of a global election. You can steal an election.”

Byers Market Newsletter

Get breaking news and insider analysis on the rapidly changing world of media and technology right to your inbox.

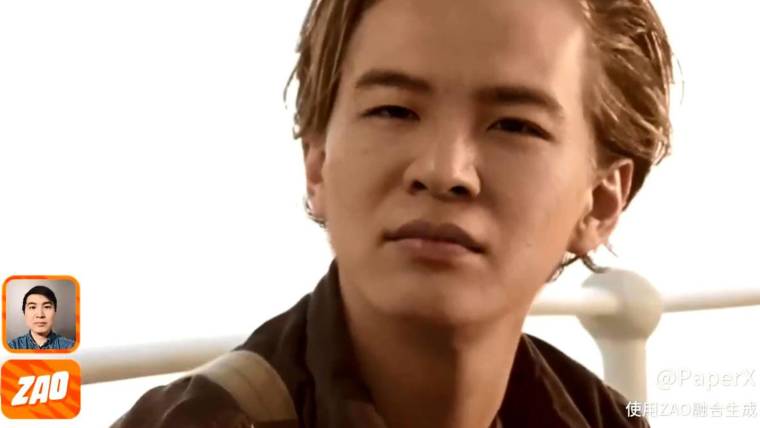

Deepfake videos made with artificial intelligence can be a powerful force because they make it appear that someone did or said something that they never did, altering how the viewers see politicians, corporate executives, celebrities and other public figures.The tools necessary to make these videos are available online, with some people making celebrity mashups and one app offering to insert users’ faces into famous movie scenes.

And the influence of deepfake videos may only grow as the 2020 election approaches and political operatives seek an edge online, a prospect that has researchers racing to find a way to accurately and quickly identify videos that have been doctored and try to shore up the public’s trust in what they’re seeing.

“It’s not really possible to stop the technology. We are in a race between the artificial intelligence to detect it and the artificial intelligence to perfect it,” House Intelligence Committee Chairman Adam Schiff, D-Calif., told the “TODAY” show in June.

In October, Sens. Marco Rubio, R-Fla., and Mark Warner, D-Va., sent a letter to social media companies urging them to come up with clear policies about deepfakes.

It can be a challenge to determine whether any one video has been manipulated, but Farid’s team is trying an approach based on spotting subtle patterns in how people speak. By feeding hours of video into their system, Farid said they’ve been able to identify distinctive verbal and facial tics — known as soft biometrics — for President Donald Trump and various Democratic presidential candidates.

The power of distorted video was underscored in May, when a doctored video surfaced online appearing to show House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., having trouble speaking. The video was relatively simple in its distortion compared to deepfakes made with artificial intelligence, but the speed with which it spread made it clear how unprepared some tech companies, news organizations and consumers were for the new technology.

Other deepfakes have also gained traction, though some have helped educate the public on the existence of deepfake technology. Actor Jordan Peele portrayed Obama in a doctored video that spread widely last year, and more recent examples of deepfakes include ones involving actor and politician Arnold Schwarzenegger and Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg.

Big tech companies such as Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and Reddit have struggled to come up with an effective and consistent response, sometimes removing the videos or slowing their spread and other times not.

Pelosi accused Facebook, in particular, of “lying to the public” after the social media company said it would leave up the distorted video of her, though the company said it would reduce how often the video appeared in people’s news feeds.

Now, Facebook is helping to fund labs like Farid’s to get academic help on the problem of identifying deepfakes. This month, Facebook said it was providing researchers with a new, unique data set of 100,000-plus videos to aid research on deepfakes.

Farid has a track record of pushing tech companies to do more to remove problematic material. In a previous project to fight online extremism, he developed software for social media services to use to flag images and other posts supporting the Islamic State militant group and others.

With the research into deepfakes, Farid’s algorithm is built to help researchers and news organizations such as NBC News spot deepfakes of candidates in the 2020 presidential race. They’ll be able to upload videos via an online portal, he said.

“The hope is when videos start getting released, we can say, ‘This is consistent; this is inconsistent,'” he said.