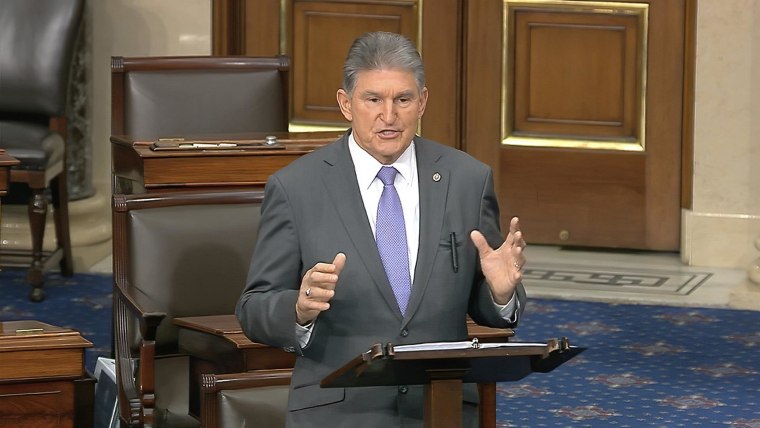

As the Senate prepares for its final impeachment vote Wednesday — a vote that, by all accounts, will acquit President Donald Trump — Democrats are scrambling to find other ways to hold Trump accountable. One suggestion, thrown out by Joe Manchin, a moderate Democratic senator from West Virginia, would be to censure Trump. Manchin said Monday that he believes that a “bipartisan majority of this body would vote to censure President Trump.”

Manchin is most likely wrong, unless private conversations with Republicans not named “Romney” hold up when exposed to the glare of Twitter. But what would a censure of Trump look like? Or accomplish? The first and only time the Senate censured a president was in 1834, when it condemned Andrew Jackson, whose portrait hangs in the Oval Office where Trump now sits.

Jackson, like Trump, read little and spelled poorly — the president he defeated in 1828, John Quincy Adams, labeled him a “barbarian.”

Jackson, like Trump, read little and spelled poorly — the president he defeated in 1828, John Quincy Adams, labeled him a “barbarian.” Jackson also had an authoritarian manner, which he’d developed as a major general, and he claimed to understand, at the gut level, all issues a president needed to confront. He boasted, swore, insulted perceived personal and political enemies and demanded unquestioned loyalty from all who served his administration. He was caricatured as “King Andrew I,” a would-be monarch. Among our early presidents, he was the one most associated with the aggrieved white common man. He was, incidentally, as he exited the presidency in his 70th year, the oldest man to have served as president up to then.

Get the think newsletter.

In 1834, exhausted by the seventh president’s antics and unpredictable outbursts, senators in the rising Whig Party blew off steam by voting to censure Jackson for withholding documents relating to a tirade he had directed at the Bank of the United States, an institution that afforded economic stability but that Jackson claimed was anti-democratic — and out to get him.

An obvious question in this murky business concerns the non-punitive character of congressional censure. The purpose of censure is to discredit both the president’s act and the motive behind it. The desirable outcome must be reformation of bad behavior. Do any “conscience” Republicans who may privately be saddened believe censure will do any good in altering the actions of the current president?

If historical example helps, Jackson did not change one iota. He was, at least on the surface, unfazed. Despite attacks from the likes of Henry Clay of Kentucky, Jackson’s chief antagonist in the Senate, Sen. Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri described Jackson as “perfectly mild in his language, cheerful in his temper, firm in his conviction.” In fact, Jackson was never known to be perfectly mild — not a day in his life. As a general facing censure back in 1819 for having exceeded his orders in Spanish Florida, he had threatened to cut off the ears of the senators who dared to investigate his behavior.

The Constitution provides for censure in the case of an errant member of Congress, but it does not specifically grant Congress the option to censure an executive whose behavior falls short of the impeachment standard. The first clear attempt to censure a president was pursued by Rep. Edward Livingston of New York against John Adams for improper interference in a judicial matter. As mayor of New York a few short years later, Livingston was implicated in a financial scandal and found a safer haven in rough-and-tumble Louisiana. There, he assisted Gen. Andrew Jackson during the Battle of New Orleans at the end of 1814, returned to Congress when Jackson was president and served his friend as secretary of state and as an occasional speechwriter in the years leading up to the Whig censure vote.

Lest anyone assume early 19th-century politics was less combative or less confusing than it is now, there were actually many more partisan-driven censure votes over the course of the century. The famously independent Rep. John Quincy Adams, who despised Jackson, opposed the Whig-led censure in 1834 because he recognized it as a purely partisan device; in 1842, Adams sought a remedy for the veto-happy President John Tyler by formally studying whether to censure him, impeach him or rein him in by constitutional amendment.

Falling short of impeachment, censure was meant as a moral statement absent any more serious punishment.

Historically, Congress (either the House or the Senate) has weighed censure of a president as a form of reprimand for one or another abuse of power. Falling short of impeachment, censure was meant as a moral statement absent any more serious punishment. Most of those attempts have gone nowhere — as will most likely happen with Trump given the Republicans’ majority. In 1972, months before the Watergate break-in, a House resolution considered censuring President Richard Nixon over his conduct in prosecuting the war in Southeast Asia.

So Congress has generally dealt with censure in a haphazard way. Modern philosophy is only slightly more informative. It tends to define an act of censure as the institutional means of informing a person that an action was morally wrong and inexcusable.

Still, in the case of Trump, the question would appear moot. His threats to the disaffected in his own party are blatant, and his divide-and-conquer approach amid demands of fealty have somehow kept a host of elected representatives in line, or at least malleable. Reporters show these members of Congress dodging direct questions when they are presented in terms of moral leadership. It is hard to imagine enough of them accepting censure to limit their exposure to unhappy voters back home.

Even if a censure vote were to succeed, the magnitude of the infraction in Trump’s ill-considered Ukraine-Biden gambit is likely to remain as debatable as before. Regardless of where senators come down on the censure question, if history is any guide, we will be in as gray an area as before Manchin floated his alternative. One can just imagine a White House spokesman brushing off reports to the contrary and insisting that Trump, like Jackson, greeted the news with his well-known cheerful temper.