As the world battles a pandemic, it seems like an odd time to consider the larger implications of the publication of Woody Allen’s memoir, which came out Monday after having been axed by his original publisher.

But in such times, when civil liberties often take a back seat to the demands of public health, this might be exactly the right moment to stress that in a democracy, we need to tread very carefully when it comes to effectively denying someone’s right to free speech.

In this country, we don’t use censorship to punish people. Even convicted murderers get to write books.

Allen’s nearly censored book, “Apropos of Nothing,” was finally released by Arcade Publishing after Hachette Books, Allen’s previous publisher, backed out in the face of loud protests by his son Ronan Farrow.

Farrow accused Hachette, which is also his publisher, of being “wildly unprofessional” for planning to publish the Allen memoir without giving Dylan Farrow, his sister and Allen’s adopted daughter, a chance to respond to the manuscript because she has long alleged that she was abused by Allen when she was a child. Many Hachette employees walked out in protest of the book.

Get the think newsletter.

I certainly understand Hachette’s reluctance to move forward. The publisher faced a potential onslaught of bad publicity and accusations that it was insensitive to abuse allegations, as well as being hypocritical given its recent publication of Farrow’s book “Catch and Kill” after he charged that media companies blocked his efforts to expose the predation of Harvey Weinstein.

But we use the courts rather than censorship to punish people. Free speech isn’t a reward for good behavior. It’s a right that stays meaningful only if we extend it to people we find repugnant.

And it is only more important to heed the admonition to make sure that our vigilance in protecting the vulnerable from predators doesn’t make us vigilantes when the justice system hasn’t found a person guilty.

Unlike Weinstein, Allen was investigated and wasn’t charged, although the Connecticut prosecutor in the case said he had “probable cause” to do so but wanted to spare Dylan the trauma of a trial. Investigators at Yale New Haven hospital, on the other hand, found no evidence of abuse. Even some of the director’s critics concede that no other women and children have accused him of predatory conduct.

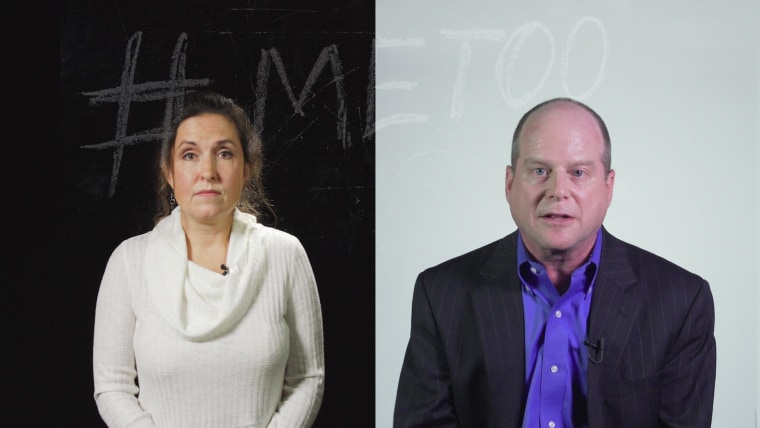

I personally have no idea whether Allen molested his daughter, though as a woman, mother and feminist in the era of #MeToo, I take seriously allegations of predatory crimes, particularly against children. I’ve written a great deal about the Catholic Church’s long history of covering up the abuse of the priests in its ranks, and if Allen is ever proven to have done something wrong, he should be punished, too — in a court of law.

Which doesn’t mean that Allen should be shielded from these allegations. Farrow and his sister have every right to continue their criticism of Allen and to encourage more scrutiny from the industry that has given him so many awards over the years.

But publishing a book doesn’t mean the author gets some seal of approval for his views or his personal conduct. It’s a business negotiation. If a publisher believes it meets its legal and editorial standards, the memoir should be published.

That also means those who object to Allen’s behavior should demonstrate their opposition by not buying the book. I certainly won’t buy it. I never was much of a fan of his films to start with, and I find his obsession with very young women to be creepy. I encourage others who find Allen’s conduct unacceptable to boycott both his books and his films. The marketplace gives us that power.

But in this country, we don’t use censorship to punish people. Even convicted murderers get to write books. The serial killer David Berkowitz worked with evangelical ministers to write “Son of Hope: The Prison Journals of David Berkowitz,” published by Morning Star Communications. You can still buy it on Amazon.

And attempts by state legislatures to prevent convicted criminals from profiting from accounts of their crimes have been restrained by the Supreme Court. In an 8-0 decision, the court struck down New York’s effort to keep convicted murders like Berkowitz from doing so as a violation of the First Amendment.

So it was a good thing that Arcade quietly released the Allen memoir Monday. In a democracy, we depend on the courts to decide guilt or innocence. We rely on readers to decide whether or not they want to hear Allen’s account of his life.