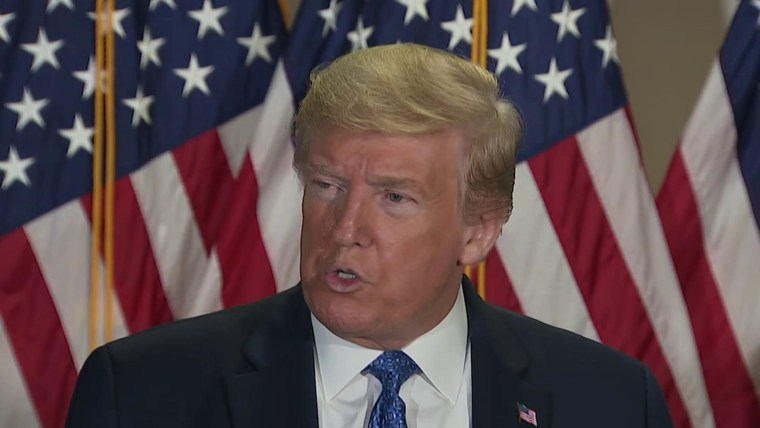

Hydroxychloroquine, the anti-malarial drug touted and previously taken by President Donald Trump to fight coronavirus, has fallen out of favor and public view as studies — like one halted Friday — have suggested it does little to treat infection while exposing users to dangerous side effects.

Not all researchers have given up on the drug, however, and recent developments show it is not yet dead as a potential weapon against COVID-19, especially as a preventative in people not yet exposed to the virus.

On Thursday, three authors retracted a widely publicized study about the use of the drug in coronavirus patients. The authors had found COVID-19 patients who took the drug were more likely to die. After its publication in the influential British medical journal The Lancet, however, the authors faced criticism over their data.

When the company that supplied the data declined to provide the full data set and other information for review, three of the study’s four authors wrote, “Based on this development, we can no longer vouch for the veracity of the primary data sources.”

A day earlier, the World Health Organization recommended that its researchers continue to study the drugs’ potential use against coronavirus, restarting a paused trial.

And researchers across the U.S. are still testing the drug. The 48 or more trials still underway include at least 17 that are testing whether it could still play a role as a prophylactic preventing COVID-19 infection, even if it may not help treat patients who are already infected with the coronavirus.

On Wednesday, the New England Journal of Medicine published the results of a University of Minnesota trial that showed the drug did not help prevent COVID-19 trial in patients who were already exposed to the virus.

Dr. Bradley Connor, the lead investigator for The New York Center for Travel and Tropical Medicine’s trial, was undeterred by the Minnesota results. “Science is based on multiple studies. This doesn’t change anything.”

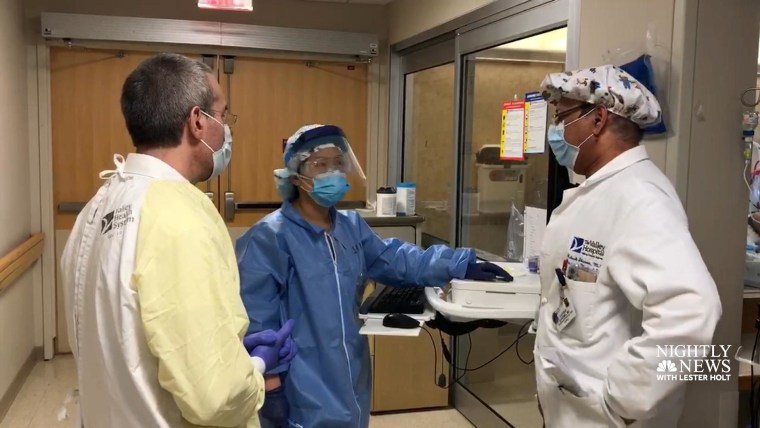

Connor’s trial examines whether hydroxychloroquine could be a prophylactic prior to exposure to the virus. “I think this deserves further study given the preliminary data from Europe and the in-vitro data would suggest that we need more information.” Connor says enrollment for his team’s double-blinded, randomized placebo-controlled trial is set to begin over the next two weeks and is focused on pre-exposure for healthcare workers.

With eyes on the drug’s preventative role, teams at Duke University Medical Center, ProHEALTH and UnitedHealth Group, NYU Langone Health in New York and Hackensack Meridian Health Corporation in New Jersey tell NBC News they’re continuing or have concluded their trials regardless of recent findings.

A decades-old drug, hydroxychloroquine is traditionally used to treat autoimmune disorders including lupus and arthritis medicine and is also prescribed to prevent malaria. Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, there was evidence the medication might help treat patients with the coronavirus.

Let our news meet your inbox. The news and stories that matters, delivered weekday mornings.

It’s known to have side effects, including muscle weakness and heart arrhythmia, although experts say it’s generally considered safe for a healthy population as long as it’s not prescribed with other medications that could cause arrhythmias.

The University of Minnesota’s study of the antimalarial did not find serious side effects such as cardiac complications, though participants were more likely to have minor gastrointestinal effects like nausea or diarrhea.

Experts say that data point is critical.

“The main takeaway from this study is that hydroxychloroquine, as we suspected, is generally safe. Although the drug did not show a statistically significant benefit when people took it immediately after exposure, it may still have a benefit for prevention prior to exposure,” says Dr. Adrian Hernandez, principal investigator of the HERO research program coordinated by the Duke Clinical Research Institute. Compared to the Minnesota study, the HERO study will give the drug earlier and for a longer duration — 30 days instead of five days.

“This is a well done, really informative study,” says Dr. Daniel Griffin, chief of infectious disease for UnitedHealth Group and ProHEALTH New York. Griffin is leading a two-pronged trial of hydroxychloroquine’s effectiveness preventatively as well as in patients taking it within the first day or two of illness.

In early April, when Griffin’s team first took up their trial, many people had already begun taking the anti-malarial. “It wasn’t so much that I was impressed by any early data,” he said. “It was more that I realized that this was something that people were using. And it was really important to know whether or not it was safe and effective.”

“The reason I say I don’t think it’s a nail in the coffin is that, fortunately, they didn’t find any serious adverse effects … no one’s actually being killed by hydroxychloroquine and that’s what I think puts a nail in the coffin.”

Dr. Michael Belmont, medical director at NYU Langone Orthopedic Hospital, says he is “not especially encouraged, given the experience with active treatment, given the experience with post-exposure prophylaxis, but I still want to complete my study looking at pre-exposure prophylaxis.”

Belmont is the principal investigator of NYU Langone Health’s ongoing trial of hydroxychloroquine for pre-exposure prophylaxis.

Belmont says he has used the drug on rheumatoid arthritis and lupus patients for 35 years without much short-term toxicity, adding that he still sees a possibility that a lower dosage of the drug may prevail in “reducing either the occurrence of symptomatic infection at all, or at least have a mitigating effect so for those that become symptomatic it’s less likely they’ll require hospitalization, ICU, and intubation.”

Politics meets science

Hydroxychloroquine initially became a lightning rod after Trump repeatedly touted it as a preventative measure against the virus. On Wednesday, the White House released results of the president’s latest physical, including that he had taken a two-week course of the drug as well as zinc and vitamin D following the COVID-19 diagnosis of two West Wing staffers.

Medical teams tell NBC News the politicization of the drug has complicated the trial enrollment processes.

“It’s become quite a challenge I think to enroll people in a lot of these trials and actually ever find out if it is particularly attractive preventative or early treatment,” Griffin said.

In his study’s case, initial enrollment was set at 850 participants, although the team is not enrolling new people at the moment. Instead, it’s monitoring the 50 or so participants already enrolled, most of which are healthcare workers. So far, Griffin says there is no evidence of harm or serious adverse effects caused by the trial.

“What we found in our trials was a combination of people not being interested in enrolling, a number of people withdrawing from the trials because either they were concerned or their physician was concerned — and so we ended up in our trials with very limited enrollment,” Griffin explained.

Belmont says while his trial is still on track for completion this September, his team’s experience recruiting their initial target of 350 healthcare worker participants has been similarly paused.

Over the course of recruitment, initial enthusiasm for hydroxychloroquine in active treatment waned and the overall number of acutely ill COVID-19 patients entering NYU’s medical center and exposing themselves to workers declined. Currently there are about 100 participants enrolled in the trial after some workers opted to provide blood samples for the trial’s observational arm instead of taking the drug.

As a result, said Belmont, “I fear I may have lost the ability” to demonstrate a meaningful effect of hydroxychloroquine on acquiring the infection, “but that’s the reality of doing clinical science.” He still hopes to provide insight into how patients tolerate the drug and address other exploratory goals.

Still, at least five groups previously conducting clinical trials of hydroxychloroquine on healthcare workers told NBC News their teams had failed to be approved by review boards, withdrawn, or suspended their trials due to recent trial results, safety concerns or difficulty in enrolling participants.

Montefiore Medical Center in New York officially withdrew its trial of the drug’s treatment of healthcare workers after it was deferred by its IRB, or review board. The study’s principal investigator, Dr. Priya Nori told NBC News, “We didn’t pursue the study further because we just didn’t feel it was worthwhile.” Nori said that hydroxychloroquine was removed from the center’s treatment protocols weeks ago.

Texas Cardiac Arrhythmia Research Foundation in Austin also withdrew its proposal before receiving approval due to safety concerns. Dr. Adam Singer of Stony Brook University in New York said his team did not move forward with its approved trial because “we cannot get healthcare workers to agree to participate in the study.”

In anticipation of a possible second wave of the virus in the fall, Griffin said his team will continue to engage therapies beyond hydroxychloroquine. “As each week, as each month goes by, my hope is that there are more things that are being developed specifically for COVID-19, with even more exciting potential therapeutics and prophylactic medicines that we may want to focus our resources on.”